In business, the right question can often be the best answer

An unusual look at the economic and interpersonal consequences of deflecting direct questions

One of the most difficult moments in life occurs when confronting a question one wishes had never been asked. From job interviews to meetings with bosses to business negotiations, there are endless examples of questions where a fully honest response could result, at best, in an economic loss or, at worst, in the destruction of an entire relationship.

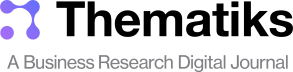

Take, for example, a recently-married female job candidate who is asked about plans to have children in the future. She could answer honestly: “I plan to have children in the next year.” She could refuse to answer: “I would rather not say.” She could lie: “I don’t plan to have children any time soon.” Researchers have examined the implications and consequences of each of these three types of responses, but a fourth option also exists —deflection, i.e., responding to the original question with yet another question that attempts to take the conversation in a different direction.

The consequences of choosing deflection in response to an unwanted question are the focus of research from T. Bradford Bitterly (Hong Kong Technical University) and Maurice E. Schweitzer (Wharton). Their research conclusions are worth considering, given that difficult questions are still very much a part of everyday life.

Their paper begins by noting that declining to answer a question directly risks two possible penalties. First, someone may incur an “interpersonal” cost, e.g., the risk of being seen as less forthright or trustworthy. Second, someone may incur an economic cost, e.g., receiving an offer of a lower salary. These risks arise from the information asymmetry that can be present in certain discussions, e.g., where one party has information that, if revealed, could benefit a counterparty or even cause them harm. The authors label these interactions strategic disclosure interactions. They note that in these situations “individuals are motivated to conceal sensitive information, but the likelihood of disclosure may be profoundly influenced by contextual factors such as competition, social pressure, financial incentives, and even the medium of communication.”

In these settings, even individuals who want to disclose all the requested information may not do so for fear that doing so may bring a heavy cost. As the authors note:

In a negotiation, for example, someone who fully discloses their private information may be exploited by their counterpart. Similarly, in a job interview, someone who truthfully responds to a sensitive question (e.g., how much they made in their last position or about drug use) may be offered a lower salary or fail to receive an offer. In settings involving sensitive information, people often feel compelled to respond when they are asked a direct question, but may suffer economic costs when they do.

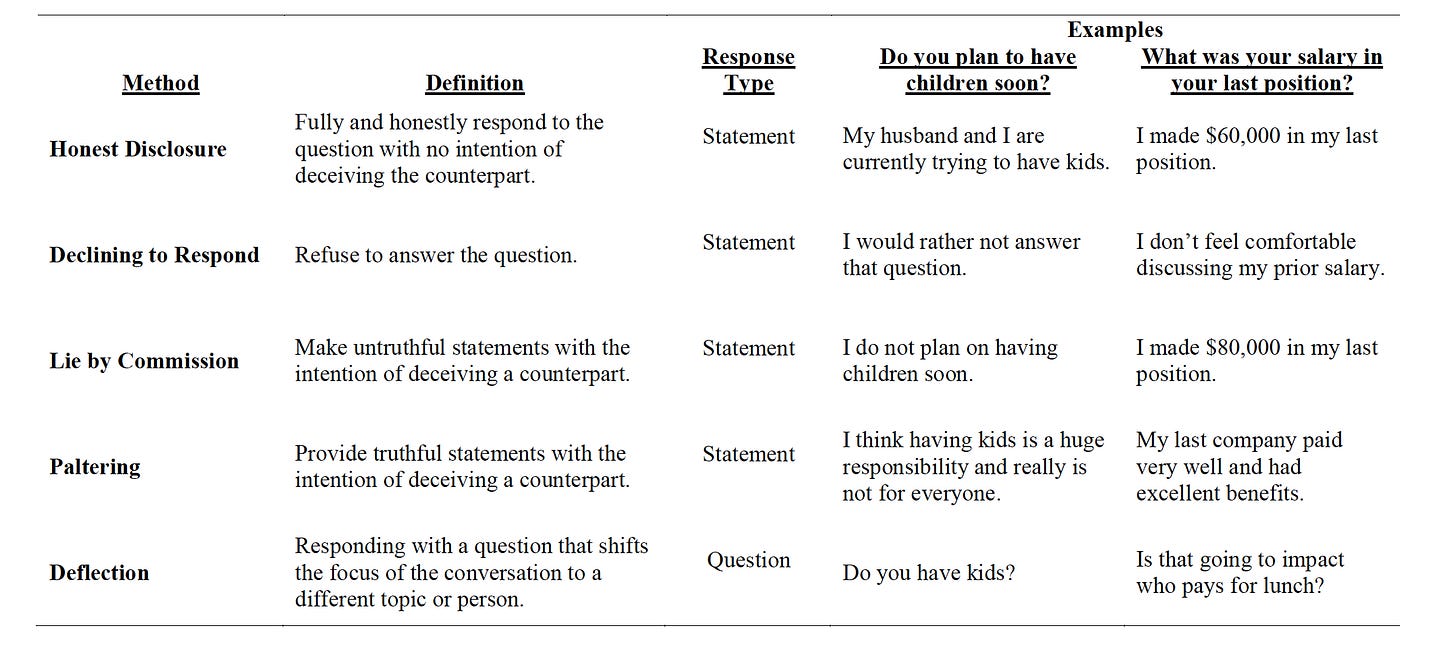

The challenge for people asked an uncomfortable question is to respond in such a way that does not put them in jeopardy. Refusing to answer is not an ideal response, since research has shown that people who decline to answer direct questions are viewed as less trustworthy and less likable than individuals who disclose sensitive information. In addition, individuals who decline to answer sensitive questions often reveal information just by declining. For example, someone who responds, “I do not want to answer that question” after having been asked, “Have you ever been convicted of a felony?” suggests an answer that is not very hard to divine. Alternatively, note the authors, individuals may respond to a question by engaging in lying, but individuals who engage in deception risk harm to their long-term relationships should the deception be discovered. Indeed, lying and subsequently being found to be a liar is probably the worst possible outcome.

Given that lying is such a risky (and unethical) option and that refusing to answer may be almost as bad as answering, what, the authors ask, are the consequences of deflecting?

The Studies

To answer the main question of their research the authors conducted a series of studies to assess the impact of various response strategies. The three studies were broadly similar in approach and methodology. In the pilot study, for example, they recruited 99 individuals to ask a job seeker to disclose his salary at his previous job. Some respondents gave an honest answer, and some deflected with the question: “Will the answer impact who pays for the coffee?”

The 99 participants then rated each candidate along several interpersonal dimensions such as warmth, competence, trustworthiness, and likability. The authors also asked participants to rate the extent to which a candidate’s response was “appropriate,” “funny,” “humorous,” and “suitable.”

The authors found that job seekers were rated as warmer, more competent, more trustworthy, and more likable when they deflected than when they refused to answer a direct question. Participants also rated the deflection as “funnier and more appropriate” than a direct refusal.

Their next study was more complex. In this experiment, the authors asked 232 people to imagine that they were the owner of an art gallery negotiating the sale of the last available painting in a set of four works by a well-known artist. The participants were told that a buyer who had the first three pieces in the set would pay much more for the last piece than someone who did not have other works in the collection. Thus, a buyer’s other holdings in the series became a key piece of information they needed to gather. When asked, some buyers refused to disclose other holdings in the set: “I’m not prepared to discuss my collection right now.” In other cases, the buyer admitted to ownership: “I did purchase the other Hearts pieces in the collection.” In a third group, the buyer deflected: “How much do you want for this piece?”

As in the first study, deflection proved to be the response with the best interpersonal and economic outcomes. Deflectors paid less for the painting than those who answered directly and deflectors were perceived as more trustworthy than those who refused to answer. As the authors note:

In the deflection condition, only 12% of the participants asked the buyer more than once if they had the other pieces in the Hearts collection. Deflection was also very effective at concealing information. Individuals thought that individuals who deflected questions were less likely to have the other pieces in the collection than individuals who explicitly declined to answer the question and individuals who disclosed information about their collection. The disclosure of this sensitive information directly increased economic surplus for individuals who deflected.

In their final study, the researchers introduced a different response strategy known as paltering. Paltering occurs when one uses statements that are in themselves true to create a misleading impression. For example, someone asked if she planned to have children palters by replying “children are a big responsibility” or “children need parents who are secure in their careers.”

Figure 1: Summary of the methods of responding to direct questions during strategic disclosure interactions. (Source: Authors)

In this last study, 304 people completed much the same process in the study noted above. However, in this final experiment, both deflection and paltering were tested. Some buyers deflected: “Can you tell me more about this piece? What price are you asking for it?” Some buyers paltered: “I’ve been looking to buy one.” A final group lied in response to the ownership question: “No, I do not have any other pieces in the set.”

The results of the final study indicate that deception created the most economic value and favorable interpersonal impressions up until the moment the lie was discovered. At this point, the outcomes became the worst of all. That is, “after revealing the truth about the buyer’s history and interests, the sellers’ ratings of the buyers’ trust and likeability were significantly lower.” In contrast to engaging in deception, however, “deflection had lower interpersonal costs after participants discovered that the buyer had other pieces in the collection.” Moreover, much as with deception, paltering yielded positive outcomes until the truth was discovered, after which it created similar outcomes as lying.

Figure 2: Summary of the economic and interpersonal costs of the methods of responding to direct questions during strategic disclosure interactions. (Source: Authors)

All in all, across the various studies, participants were more willing to negotiate with individuals who deflected because sellers viewed that negotiator as more likable and more trustworthy. That is, they viewed the buyer who deflected as “having concealed less information about their collection than the buyers who engaged in deception.”

Conclusions

The late linguist Paul Grice described rules that people intuitively follow to make their communicative efforts effective. The four Gricean maxims are:

The maxim of quantity, where one tries to be as informative as possible, giving as much information as is needed, and no more.

The maxim of quality, where one tries to be truthful and does not give information that is false or that is not supported by evidence.

The maxim of relation, where one tries to be relevant, saying only things that are pertinent to the discussion.

The maxim of manner, when one tries to be as clear, brief, and as orderly as one can in what one says, avoiding obscurity and ambiguity.

The authors note that deflection paradoxically both violates and invokes the second maxim. By redirecting the conversation, deflection enables individuals to conceal information they do not wish to share, while at the same time requesting similarly valuable information from their counterpart. The authors’ research suggests that when faced with an unwanted question or a question that would put someone at a disadvantage in a negotiation, deflection is the optimal response. As the authors conclude: “By responding to a question with a question, individuals can maintain favorable interpersonal impressions, capture economic surplus by avoiding revealing potentially costly economic information, and avoid the risks inherent in using deception.” Moreover, the value of deflection is even higher in those situations where even a non-answer becomes an answer. For example, “when an employer asks a prospective employee if they have ever been convicted of a felony or a negotiator asks the other party if they have other offers, explicitly declining to answer reveals information.”

In closing their paper, the authors caution that effective deflection is not so easy as it may seem. As they note, conversation norms guide individuals to answer questions directly; thus, "it may require effort and practice to both violate and invoke this conversational norm by deflecting a difficult question." On the other side of the conversation, "interviewers, negotiators, and debate moderators should anticipate and guard against deflection." In addition, questioners should recognize that deflection may yet convey information; specifically, “someone who deflects reveals that [he] would prefer to avoid discussing the topic.” Moreover, if deflective questions are delivered defensively or with anger, they could signal the very thing that the deflector is trying to avoid saying. That said, the authors conclude their paper by noting that sometimes the best way to answer a question may be to pose a new one.

Of course, no discussion on deflection is complete without noting the arena in which it is encountered most often: politics. Deflection has become such an overused tactic in political debates and discourse that anyone might wonder if it is still of any value in other settings. Unfortunately, the authors do not address this question; nor do they address the ethical implications of avoiding a direct answer when one is possible. Indeed, it is interesting to consider which is worse: deflection or hurting someone with an honest answer? The latter may be the purer response, but even the most severe moralist might admit that there are questions in life that are best left unanswered.

The Research

Bitterly, T. B., & Schweitzer, M. E. (2020). The economic and interpersonal consequences of deflecting direct questions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(5), 945–990. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000200