Information rich, attention poor: the danger of information overload

Research shows that ignoring the negative effects of information overload can lead to terrible outcomes, especially as decisions fail to correct a problem

Information overload ("IO") is a common term to most managers, but few of us have ever stopped to consider what the term really means and what impact it may have on our decision-making processes. Professor Peter Gordon Roetzel has studied IO extensively (and especially in the context of decision-support systems) and defines it thus:

Information overload is a state in which a decision-maker faces a set of information (i.e., an information load with informational characteristics such as an amount, a complexity, and a level of redundancy, contradiction and inconsistency) comprising the accumulation of individual informational cues of differing size and complexity that inhibit the decision maker's ability to optimally determine the best possible decision. The suboptimal use of information is caused by the limitation of scarce individual resources. A scarce resource can be limited individual characteristics (such as serial processing ability, limited short-term memory) or limited task-related equipment (e.g., time to make a decision, budget).

There is a lot to unpack in Roetzel's statement, so let's take it one step at a time.

The first part of his definition posits that IO arises when the information that a given individual receives crosses certain thresholds that make it difficult, if not impossible, to process it correctly. These thresholds, in his view, are as follows:

Quantity

Complexity

Redundancy

Contradiction

Inconsistency

Roetzel does not claim the list to be exhaustive, and we can add at least three other factors that could trigger IO:

Velocity, i.e., the rate of obsolescence of the information makes it difficult or even impossible to process

Accessibility, i.e., the information can only be processed through the acquisition of specialized skills

Bias, i.e., information is consciously (or unconsciously) presented to drive a specific outcome

Whether considering technical innovations like distributed ledgers or social movements for environmental justice, business leaders are surrounded by issues that, unless addressed with care and intelligence, will trigger IO within even the most sophisticated executive.

One might be tempted to assume that IO is simply a "fact of life" and can be ignored, but that's hardly the case for a reason we can understand intuitively, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Decision-making performance at and beyond the IO threshold. (Source: Peter Roetzel)

The figure illustrates a critical point: that as information loads approach the point at which they can no longer be processed effectively (for whatever reason), decision-making performance begins to deteriorate. This change in performance occurs because the decision-maker is able to process less and less of the total information available to help make good decisions. In other words, imagine a scenario in which making the right choice requires an executive to process ten pieces of information, the maximum amount manageable by this particular leader. Suddenly, because of a competitor’s major innovation, the necessary information load increases from ten to twenty pieces. In this case, the decision-maker who was maxed out at ten analytical tasks (100%) is forced to shift and make a decision at only 50% capacity. As the required information count climbs higher, the processing capacity percentage drops, thus generating a greater probability of making a bad choice.

Decision-makers in the situation described above experience what the American executive Herbert Simon described as "a wealth of information [that] creates a poverty of attention." This attention-deficit creates "a need to allocate that attention efficiently among the overabundance of information sources that might consume it."

There is no senior executive who has not faced this dilemma. Perhaps an issue was manageable for years until a disruptive competitor suddenly created the need for more information to properly manage it. Or an entirely new social or environmental phenomenon appears and, because of its novelty, executives must scramble to gather and process the information needed to respect this new force when making decisions. In either case, managers are confronted with a high-stakes (and often exasperating) challenge to "get up to speed" quickly and, even more critically, correctly.

Addressing the challenge inadequately is all too easy, of course. Executives can rely on poor information sources, or they can waste months or even years of effort analyzing the wrong information. Or they can also process brand new content with out-of-date skill sets, only to find out later that their analyses missed critical elements and so drew incorrect conclusions. Roetzl notes that in these situations, managers can harm not only themselves but others:

Users seem to ignore possible side effects of information overload up to a very high level before retreating from these channels or platforms. From a bird's eye perspective, this situation might be compared with the spread of a disease. Thus, people often act irrationally by infecting others (i.e., sending more messages, likes, news to other members of their network) instead of sparing themselves (i.e., making a rest/recovery from their overloaded status).

The biological metaphor is not unwarranted. Indeed, Edward Hallowell, a psychiatrist and expert on attention-deficit disorders, has observed what he calls an "attention deficit trait" in managers that presents similarly to the medical condition often seen in children and adults. Author Linda Stone, who coined the term "continuous partial attention," has noted that the inability to process something as simple as an e-mail inbox can lead to what she calls e-mail apnea: "The unconscious suspension of regular and steady breathing when people tackle their e-mail."

While the sheer volume of information is the main driver of IO, there are other factors at play as well. Researchers have noted that the trend over the last few decades to flatten organizations has increased the number of direct reports executives are forced to manage. Indeed, there are CEOs who now manage over a dozen individual executives directly, each overseeing a complex function. In turn, each direct report creates yet an additional information flow to process, compounding the organizational information overload facing any executive arising from her own functional responsibilities.

IO Under Negative Escalation

Intriguingly, there may be one other IO-related phenomenon at play in the examples above, and it is related to how IO affects decision-makers when their situation deteriorates. Roetzl and his colleagues Pedell Burkhard and Daniel Groninger recently looked at this question. They found that when someone's course of action does not yield the desired results, IO has an increasingly negative effect, which in turn leads to further bad decisions. As their paper notes:

The finding of a significant interaction between the type of feedback and the information load extends our knowledge about the role of information processing in decision-making in escalation situations. Furthermore, we find that the type of feedback affects self-justification, and we find a negative and significant interaction between information load and self-justification in negative-feedback cases.

To understand the implication of this finding, consider a retailer back in the 2000s reacting to the rise of Amazon. Sensing that Amazon is a threat, the incumbent CEO begins to react in the ways he knows: discounting, coupons, more advertising, etc. All the responses fail, and now the competitor finds himself trying to understand not just Amazon's innovations but the reasons his responses failed. His information load has increased even more than when he was not responding. This increased level of IO can progress to a point where recovery is impossible, and the CEO becomes destined to fail completely. Much like a pilot who, in a crisis, becomes overwhelmed by cockpit alarms when corrective maneuvers fail, it's precisely when strategies do not go as planned that we are most vulnerable to the negative, or even catastrophic, impacts of IO.

Conclusions

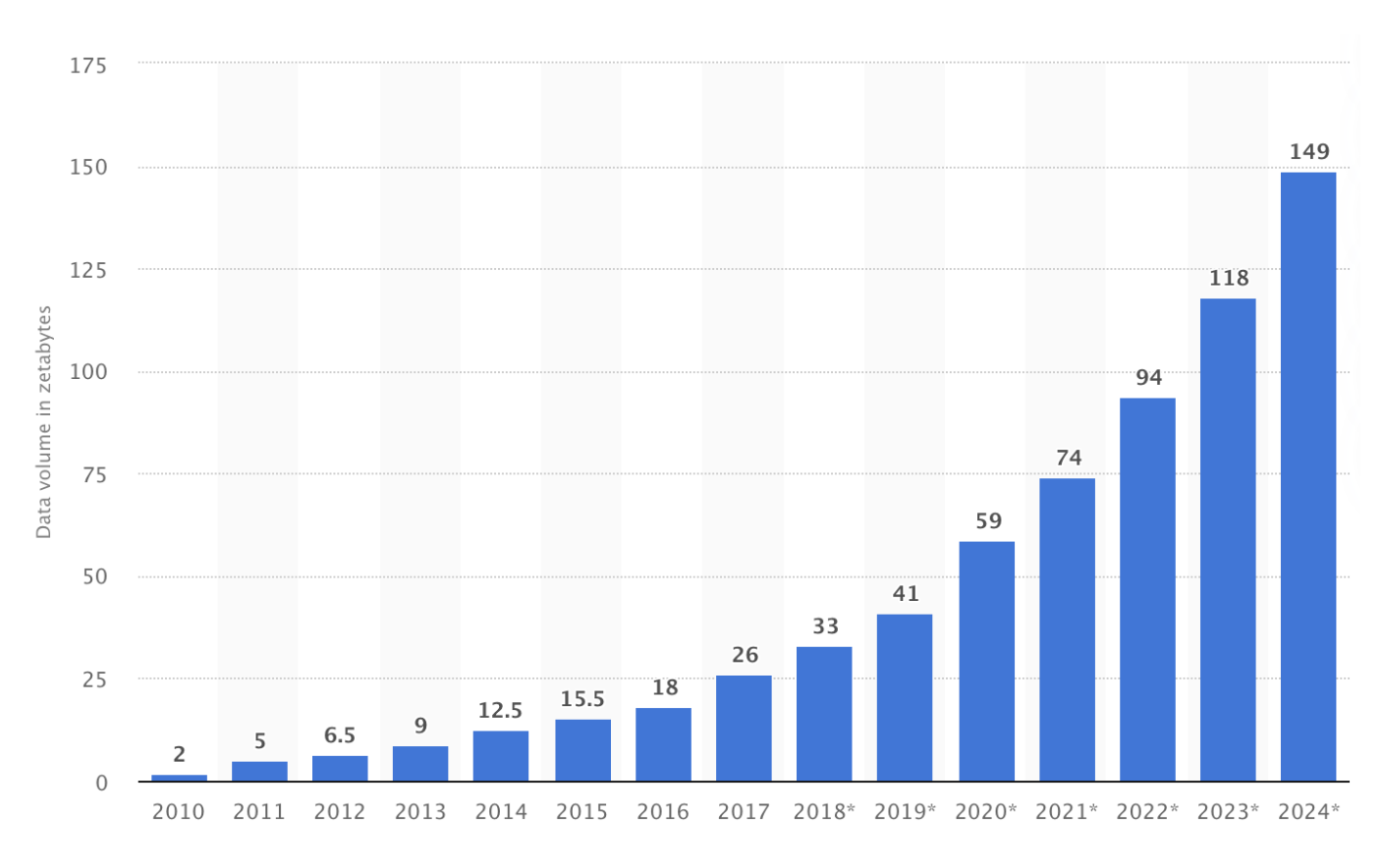

Human beings enjoy an unlimited capacity for creating new combinations of words and ideas and long, it seems, to let them out into the world. Consider that the total amount of data created, captured, copied, and consumed each year in the world is forecast to increase to somewhere around 150 zettabytes by the year 2024. Not too long ago, “one gig” was a wealth of information. Today, it is but a tiny fraction (one trillionth) of the total information produced in one year.

Figure 2: Volume of data created, captured, copied, and consumed worldwide from 2010 to 2024 (in zettabytes) (Source: Statista)

Every day, ideas are born and released into the world – most to fade into obscurity, and a few to change society forever. For a business leader, most of that new information is easily ignored. On the other hand, some of that information is critical to innovation, market leadership, or even just a company’s survival. An executive’s challenge is, of course, how to tell one from the other. How do we know whether the information we encounter signals a sea-change in our environment, is a critical imperative, or just a rehash of tired notions gift-wrapped in new terms? How do we, as leaders, decipher the information that shouts to us every day from within books, articles, lectures, webinars, magazines, peers, consultants, conferences, white papers, and websites? Is that even possible in today’s world?

While it is tempting to say “it’s not,” and move on, this position is not an option for today’s global business leaders. As Roetzl's research illustrates, ignoring IO is a dangerous game. Indeed, I contacted Dr. Roetzl after reading his papers and asked when his interest in this topic originated. He informed me that it began during his time as an Air Force officer. It was in that role where he saw first-hand how generals struggled to make sense of the torrent of information they were expected to process and the negative consequences of failing at that task. Today he focuses a lot of his work on helping software companies design user interfaces that alleviate the IO issues raised by new management information systems that too often hurt business decision-making more than they help it.

I hope Roetzl and others will continue to shed light on IO and how it shapes decision-making in our ever-expanding world of information. Executives, for their part, should seek to understand how increasing information processing loads impact their decision-making and that of their most important leaders.

The Research

Roetzel, P.G. Information overload in the information age: a review of the literature from business administration, business psychology, and related disciplines with a bibliometric approach and framework development. Business Research 12,479–522 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40685-018-0069-z