The Art of (Price) War: a perspective from China

First seen in the 90s, Chinese price wars have been in the news in 2021, and research explains the enduring appeal of this unique competitive strategy

In Western management theory, there is almost unanimous consensus that price wars are best avoided because they can have devastating (often unintended) consequences for participants. In China, of course, price wars are an accepted part of business life. In fact, this year has seen Chinese price wars in various sectors, from e-commerce, to financial services, to automotive, to commodities. Vanguard's case is especially ironic: a pioneer in low-cost investing in the U.S., it had to pull out of China earlier this year, and its remaining robo-consulting joint venture with Ant Group finds itself under extreme price pressure from local rivals such as Huatai Securities.

Reading the recent price war headlines brought to mind a paper from Z. John Zhang (Wharton) and Dongsheng Zhou (CEIBS). Though the paper is over a decade old, its analysis of price wars is still worth reading to understand how they work and why they persist.

Anatomy of Two Price Wars

The authors start their analysis by noting that in China price wars are a legitimate competitive tactic. The authors hypothesize that managers there have a cultural affinity for thinking of business in military terms, which leads them to see price wars differently from their Western counterparts. As they noted back in 2007:

It is not uncommon for today's executives to talk about the "business arena" as the "battleground," and they do not just talk about it metaphorically, either. In fact, strategy in Chinese, "zhanlue," literally means "battle plans" or "combat strategies." The rub is that while Western companies seem to suffer whenever they start, or they are caught in, a price war, Chinese companies seem to thrive on price wars they start and many emerge from them stronger, bigger, and more profitable.

The authors argue that Chinese managers’ view of price wars leads them to a different understanding of their dynamics and a better set of tactics to deploy when a price war breaks out. To support their view, the authors analyze two case studies from the early days of China's ascension to the world economic stage in the 1990s.

Changhong

The first case presented focuses on Changhong, a Chinese producer of consumer electronics. The company found its TV business in an untenable position in 1995. Foreign firms from Japan and elsewhere dominated the premium end of the market, while a growing number of local firms fought for control of the middle and lower segments. With tariffs set to drop significantly in 1996, analysts predicted that in two years' time an additional 10 million units of (foreign-owned) annual capacity would enter the Chinese market, which could be a fatal blow to the company’s TV profits.

Changdong, however, had many advantages on its side. It had 17 production lines in one location, making it the biggest, the most efficient, and the most profitable TV producer in China. Changhong was also the largest manufacturer of many key components, such as plastic injections, electronic components, remote controls, etc. Moreover, as a highly vertically integrated company located in Sichuan, one of the less developed regions in China at the time, Changhong “enjoyed cost advantages and earned the highest profit margin among all domestic color TV manufacturers.” Moreover, Changhong was the first color TV manufacturer listed in China's stock market, with a high level of brand awareness and a high-quality image (among domestic brands).

After considering the competitive and regulatory landscapes, Changhong's CEO, Ni Runfeng, decided that his best competitive option was a price war. He believed that a 10% reduction in prices would be enough to squeeze his local competitors, who did not have his margins and who could no longer count on government subsidies to keep them afloat. At the other end of the market, the foreign premium brands, who enjoyed a 20% price advantage, would face two choices. They could stay out of the price war and lose market share to Changhong, or they could cut prices, thereby lowering their margins while possibly damaging the premium position of their brands.

On March 26, 1996, Changhong fired the first shot, announcing a price reduction of 8% - 18% for all its 17" –29" color TVs, and from there the price war evolved “mostly as Changhong had expected.” Some domestic competitors appealed to regulators for help, with no success. Other domestic producers cut their prices; however, they lacked Changhong's strong supplier network and could not compete across all product lines. Foreign brands such as Sony and Panasonic, refused to lower prices, as Changhong had expected, stressing quality and functionality to buyers.

Within a few months, the winner and losers in the price war began to emerge. Changhong's overall market share increased from 16.68% to 31.64%. Some medium-sized local players, TCL and Xiahua in particular, who followed Changhong quickly, also benefited, but most small domestic players endured heavy losses. As the authors note:

During January – March 1996, there were a total of 59 local brands that had sales in the one hundred largest department stores in China. By April, this number dropped to 42. In the process, the market share for these small players dropped by 15.19%. Those big domestic manufacturers who did not follow suit saw their market shares dwindling, too. Panda's market share dropped from 7.6% to 5.8% and SVA from 5.5% to 2.6%.

Foreign brands also suffered. Before the price war, imports and joint venture products accounted for 64% of the Chinese TV market. After the price war, "the market share of domestic products significantly increased with a total of around 60% by the end of 1996." By 1997, "8 out of the top 10 best selling brands in China were Chinese and three local players, Changhong, Konka, and TCL became the best selling color TV brands in China." The effect of the first-ever Chinese price war was clear to everyone: it "drastically changed the landscape in the industry in favor of Chinese companies and the CEO of Changhong, Ni Runfeng, became a hero for Chinese national industries."

Galanz

In mid-1996, it was possible to think of Changhong's CEO as someone who just "got lucky" with an audacious but very risky plan. However, the microwave oven producer Galanz showed once again the power of a price war executed correctly. From August 1996 till October 2000, "Galanz initiated five major price wars and, through them, became the world's largest microwave oven manufacturer, with about 30% of the worldwide market and 76% of the Chinese market."

Galanz's decision to initiate the second price war in August 1996 was not without its own risks. However, the company's CEO gave the green light for three main reasons:

A significant portion of Chinese households was ready to modernize their kitchen, especially with the latest appliances.

As one of the largest manufacturers in China, Galanz saw a need to reorganize the industry for future growth.

A well-planned and executed price war could help Galanz create cost advantages that would be difficult for competitors to copy.

In sum, Galanz believed that a well-managed price war would increase its sales and eliminate weak competitors that were holding the industry back.

Galanz launched its price war in August 1996 with a price reduction of as much as 40% on some of its key products. In some cases, note the authors, Galanz's price reductions were higher than their gross profit margins. Cleverly, Galanz picked August to start the price war, as it was "the off-peak selling season when manufacturers would generally downscale their production and distribution." Galanz's actions made headlines in China and were welcome by retailers, some of whom even supported Galanz by lowering their own margins to drive up sales of Galanz’s products.

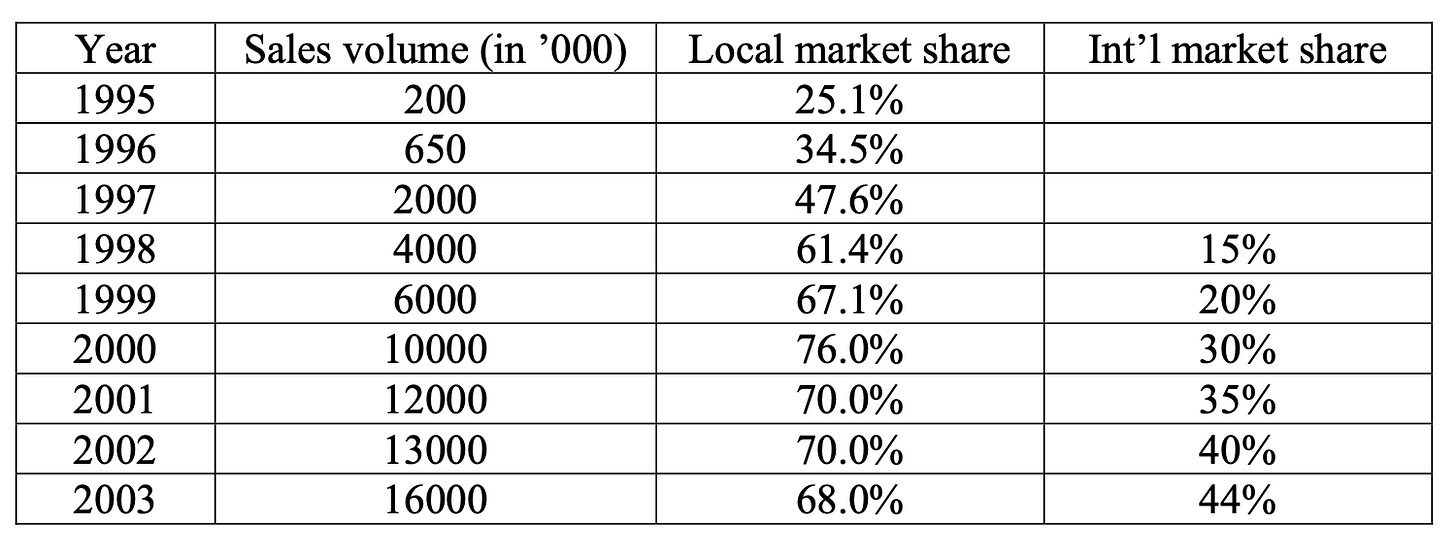

Galanz’s competitors were stunned. The small local players failed to respond initially and its largest foreign competitor, the joint venture started by U.S. company Whirlpool, was also slow to react. Consequently, by the end of 1996, Galanz's market share had grown from 25% to almost 35%, and its profits grew from cost reduction measures taken at the same time. The results of its plan were so positive that the company started four more price wars from 1997 to 2000, each time significantly cutting prices and production costs while dramatically increasing sales—a positive trend that continued, as illustrated by Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Galanz’s sales Information for the years 1995 – 2003 (Source: Authors)

Throughout the process, Galanz used a specific approach for price setting that proved devastating to its competition:

It set its price at the break-even level for its nearest competitor. For example, if the second player's annual sales were 2 million units, then Galanz would set its price at the break-even level for the 2-million units. During price wars, Galanz's price would even go significantly lower than this breakeven point. Using this strategy, Galanz always made rivals reluctant to cut prices and thus it always stayed ahead of competition in capturing more volumes. As the process unfolded, Galanz encountered fewer and fewer competitors. In 1996, there were about 120 microwave oven manufacturers. By 2003, the three largest microwave oven manufacturers took over 90% of the market.

The Art of the Price War

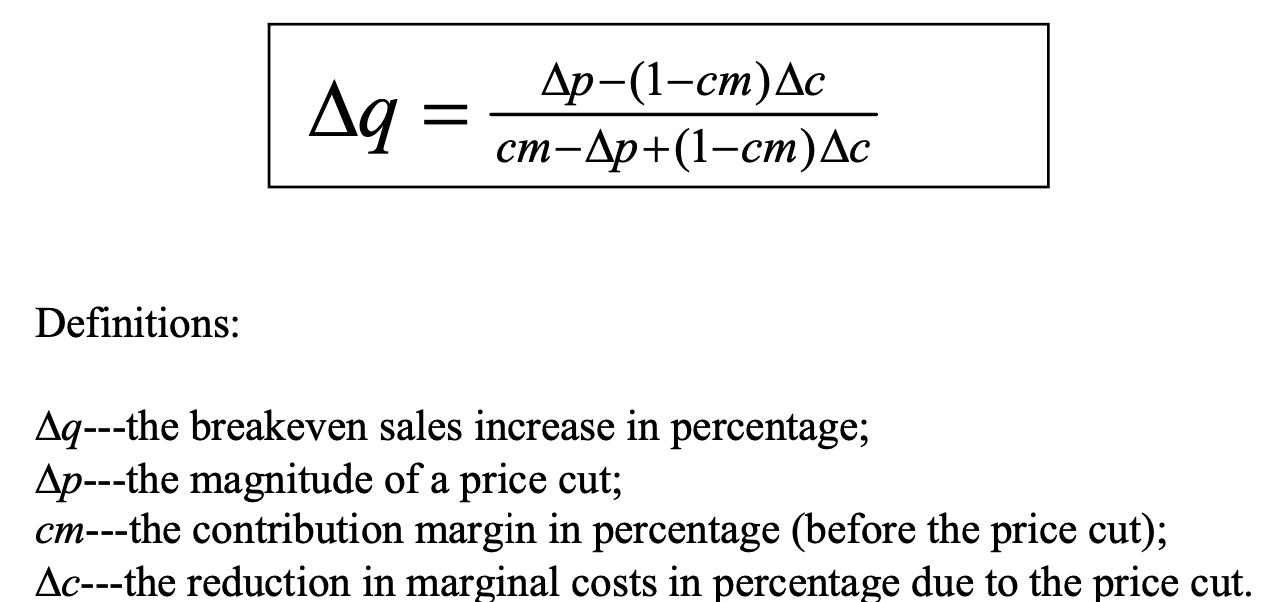

The success of Changdong and Galanz set the blueprint for how to win a price war in China, and the authors describe it in their paper. The framework is based on the use of Incremental Breakeven Analysis (IBEA), which is based on the idea that a firm can only benefit from starting a price war if its sales go up sufficiently to cover lost profits.

IBEA identifies the sales change that will allow profits (after the price change) to stay the same as before, i.e., the breakeven sales change. The formula is presented in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Incremental Breakeven Analysis (Source: Authors)

Returning to the Galanz case, the company planned to reduce its average product price by about 20% (thus, Δp=20%). Galanz's average contribution margin — the contribution per unit sales before the price change (price minus marginal cost) as the percentage of the pre-change price, was about 40% (thus, cm = 40%). The expected higher sales volume should reduce unit cost by 30-40% (thus, Δc= 35%). If one enters these values into the formula, Δq = 0.905 or 90.5%. In other words, "if the demand for Galanz's products would increase by more than 90.5% as a result of the 20% price cut, Galanz would make more profit by implementing the price cut." The only question left to answer for Galanz's CEO was if the price cuts would increase sales by 100%? He bet on the positive outcome, and Galanz easily beat that number. Thus, the authors conclude, the price war "was the rational thing to do."

The IBEA formula can be used for other analyses, the authors note, which help identify when price wars are more likely to occur. For example, across different industries, "the ones that have (unusually) high margins tend to be the ones where price wars break out, all else being equal." Additionally, in most sectors, the firm with the best margin is most incentivized to start a price war. These two insights, note the authors, explain why Chinese companies tend to start price wars when they enter the markets in the West. Chinese companies "have cost advantages and a favorable exchange rate, and they encounter a small number of competing firms in every market they enter." To them, "every business in the West is a high margin business!"

One other point is worth noting. In the IBEA formula, a larger Δp will lead to a larger Δq. This relationship simply suggests that a large price cut needs to generate a larger volume increase to break even. However, the authors explain that this relationship also tells us something about how price wars are related to product differentiation:

In a highly differentiated industry, it would take a huge price cut to persuade customers to switch from one firm to another. This, in turn, means that a huge increase in sales has to be expected in order to justify the price cut in the first place. Therefore, in a differentiated industry, price wars are less likely to break out. It is almost unnecessary to repeat the cliché here, except the fact that it conforms with the Chinese experience with price wars very well. Price wars almost always break out in an industry in China when products in the industry become standardized, with little room for further technology innovations and quality improvements.

Conclusions

"There is nothing intrinsically Chinese," note the authors, "about the calculus that Chinese executives use in planning and executing price wars." What is intrinsically Chinese, however, "is the fact that a whole generation of Chinese executives has grown up in a business environment characterized by growing markets, heterogeneous firms with a wide distribution of cost-efficiencies, and new technologies with significant scale economies." This business environment provides "many profitable opportunities for them to engage in price wars and to hone their skills.” By contrast, in Western markets, “oligopolistic competition among (mostly) equals in mature markets encourages more finesse in devising marketing strategies." In both cases, of course, managers make the rational choice.

Returning to the cases I noted at the start of the post, we see many of the same dynamics the authors detailed a decade ago still in effect. Especially in the financial services example, history repeats itself: a wealthy foreign entrant helps create a market for a new kind of product. It is attacked by low-cost local firms that push up quality, diminish product differentiation, and squeeze margins to drive out the weakest competitors. In time, the foreign innovator abandons China, leaving the local firms to fight until such time as a clear winner emerges. Because the past is prologue, the authors suggest that Western managers should understand the dynamics of price wars (as explained by IBEA) and focus on making price wars a losing proposition for Chinese competitors. Moreover, they should ignore the stigma that Western management thinkers place on price wars. In the end, a price war, in the right circumstances—and especially against a Chinese competitor—is a strategy that must be understood and, in many cases, clearly expected.

The Research

Z. John Zhang and Dongsheng Zhou. The Art of Price War: a Perspective from China. Wharton Working Paper. 2010. Available here.