The surprising power of lost alternatives

New research illuminates the surprising power that even lost alternatives can have in future negotiations

'Tis better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all.

— Alfred, Lord Tennyson

One of the most studied issues in business research is negotiation strategy. Researchers have examined this issue descriptively—seeking to understand how negotiations develop—and prescriptively—seeking to define the optimal approaches for various negotiations types and scenarios. One important issue within negotiation research is the value of any options that participants have during the negotiation process, e.g., accept, walk-away, etc. One of the most important options of all is what is known as the "Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement," (BATNA) which is simply the best option available to a negotiator should negotiations fail.

All options are defined by three dimensions: their value, their risk, and their expiration. Take, for example, someone who is granted early admission to her second-favorite college but has to respond before the response deadline of her favorite school. As in other scenarios, this applicant has to consider the quality of her second-favorite school (value), the probability that it will accept her (risk) and the last day early admissions acceptance is allowed (expiration). A job applicant with a written offer letter for a job he is willing to accept negotiating with a second possible employer has a similar set of dynamics to consider.

Research has shown that agents who have an acceptable BATNA generally do better in negotiations than those who do not have one. Strong BATNAs lead individuals to ask for higher prices and to take a more aggressive negotiating posture, for example. They are also willing to seek more value from their counterparty and to maximize the value of winning. In other words, having a positive BATNA will generally allow someone to maximize the value of a "winning hand."

Given the positive outcomes that a good BATNA can create, it is somewhat surprising that researchers have not examined what happens if a good BATNA is lost during (or just before) a negotiation, something that occurs with regularity. Does losing a good BATNA lead someone to take a lower price or assume a weaker negotiating stance? Does it impact negotiating aggressiveness or willingness to “settle for less?”

New research from Garrett L. Brady (LBS), M. Ena Inesi (LBS), and Thomas Mussweiler (LBS) looks at these questions in a comprehensive set of studies with some surprising results. The authors’ interest lies in part from the observation that, from a rational perspective, negotiators who lose an alternative are in the same position as those who never had that alternative in the first place. Logically, the authors note, "one may thus expect a lost alternative to have little effect on negotiation processes and outcomes." However, "previous research has demonstrated that negotiators’ past experiences—such as reaching an impasse in a preceding negotiation—powerfully influence the intentions with which they approach a subsequent negotiation as well as the outcomes they obtain." In light of this research, the authors hypothesized that losing a BATNA constitutes a "prior negotiation experience," and that this loss would indeed impact how people behave once the negotiation begins.

The Studies

To understand the impact of BATNA loss, the authors conducted several experiments with a total of 2,538 participants. In the first experiment, 90 individuals were asked to imagine that they were selling a VW Golf they had owned for a few years. Participants were told that the market value of the car was £10,100 and that they were about to speak with a potential buyer named Taylor. Prior to meeting with Taylor, however, a subset of the participants was informed that another buyer, Brad, had made a non-negotiable offer of £12,706 for the Golf. But just prior to their meeting with Taylor, this group was informed that Brad had walked away from the deal and would not be buying the car.

The authors predicted that participants who lost Brad's offer would set a higher target price for the Golf, and that is exactly what happened. Even though Brad's option no longer existed, it influenced the actors to try to at least match Brad's price during negotiations with Taylor.

In their second study, the authors asked 220 participants to sell a limited-edition Starbucks coffee mug valued at £10 on eBay. Prior to meeting potential buyers, they were informed that an offer of £14.50 had been made for the mug. However, five minutes later, that buyer canceled the offer, and once again the BATNA was removed. As with the first study, the second experiment demonstrated the retracted offer's clear effect on sellers, who set higher opening prices and achieved overall higher final sale prices than those who never heard the £14.50 number. As shown in Figure 1 below, even a lost BATNA can lead to higher price aspiration and a better final outcome than not having had the BATNA in the first place.

Figure1: Study 2a Negotiated Outcome for Sellers.

Studies 1 and 2 demonstrate the power of lost alternatives in a negotiation. As the authors note, "although negotiators who lost their only alternative are objectively in the exact same bargaining position as those who never had an alternative in the first place, they obtain better outcomes." How far, the authors then wondered, does this advantage go? In other words, "will a lost attractive alternative, for example, be as beneficial as an attractive alternative that is still available?"

Study 3 was designed to answer this question, and for their third experiment, the authors recruited 495 participants who were asked to manage the sale of a pharmaceutical manufacturing plant.

Participants were told that their company had purchased the plant three years ago for a “low” price of $15 million but that real estate values around the plant had declined 5% since the purchase. They were also told that failure to find a buyer would result in the dismantling of the plant and the auctioning of assets worth an estimated $17 million. In addition, participants were told that a company named Inergy had already made a $24 million offer for the plant. Unlike the other experiments, some participants were told that the Inergy bid was canceled prior to negotiation start but another group was allowed to keep this BATNA alive during the sales process. The experiment proceeded as follows:

In response to their opening offer, participants received a counter-offer from the ostensible counterpart. The first counter-offer the script gave was $16.50 million, followed by $17.50 million, $19 million, $19 million, $20.10 million, and $21.25 million. The final offer in round 7 was a take it or leave it offer worth $24.5 million. After each pre-set offer was received by participants, they had the option to either accept or reject it (and then make a counter-offer). If the participant rejected an offer (e.g., $17.50 M) and then provided an offer that had a value below the pre-set value for the next round (e.g., $18 M, which is lower than $19 M), the participant was informed that their counterpart had accepted the offer and the negotiation had ended.

The results of the third experiment were consistent with the first two studies: "negotiators who lost an attractive alternative had significantly higher aspiration levels than negotiators who never had an alternative." Further, "negotiators who had an attractive alternative [i.e., those who did not lose the Inergy bid] had significantly higher aspiration levels than negotiators who lost an attractive alternative." Again, note the authors, "negotiators who had lost an attractive alternative set higher aspirations, made more aggressive first offers, and obtained better outcomes than those who never had an alternative." Clearly, losing the attractive alternative was better than never having had it in the first place. But, as shown in Figure 2 below, "keeping the attractive alternative is better yet." Indeed, "negotiators who still had an attractive alternative set the highest aspirations, made the most aggressive first offers, and obtained the best outcomes."

Figure 2: Study 3 Negotiated Outcome for Sellers. (Source: Authors)

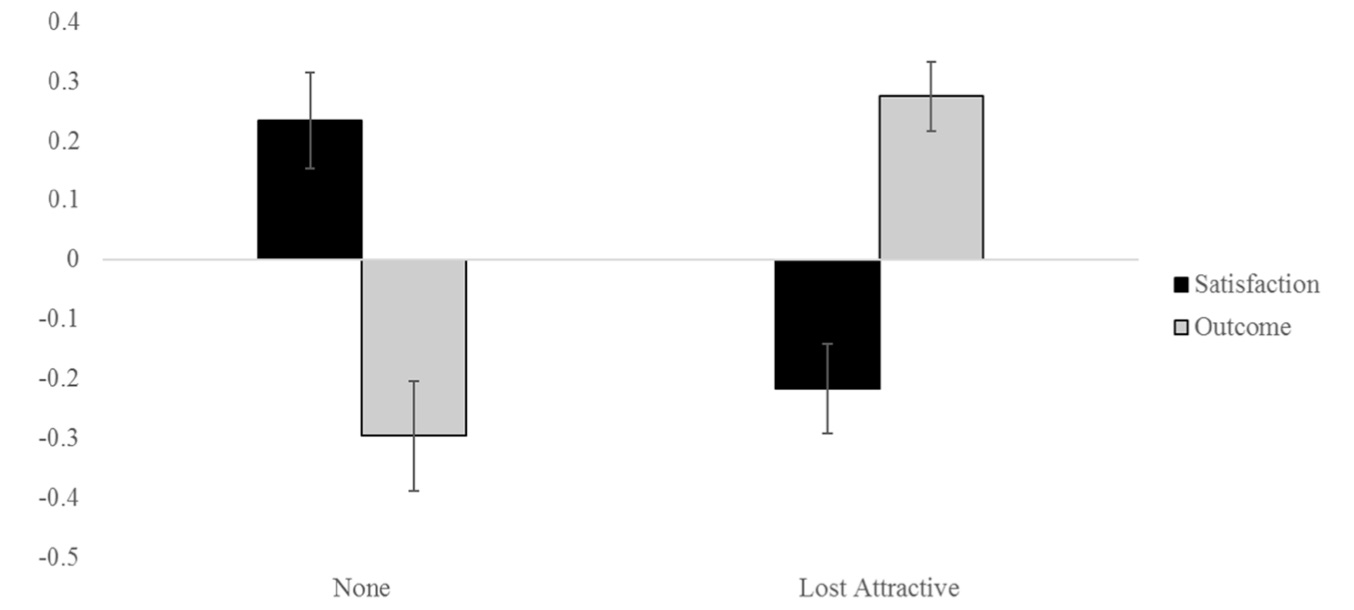

One more study is worth noting. In their sixth experiment, the authors recruited another two groups and repeated the pharmaceutical plant sale experiment. This time, the BATNA group was told about the $24 million Inergy bid, which was then removed during the sales negotiations. Once the negotiations were over, the participants were asked to rate their overall satisfaction with how the negotiations turned out.

As expected the participants who lost the BATNA performed better overall in the sales negotiations than those who never knew about the Inergy bid. However, as shown in Figure 3 below, even though they had better outcomes, the BATNA group was less satisfied with the result of the sale. The results of this final experiment, the authors note, "demonstrate that the better objective outcomes that are typically obtained by negotiators who lost an attractive alternative do not necessarily lead to higher levels of satisfaction." Instead, these findings "are in line with previous research demonstrating that those who do better in negotiations because they set higher aspirations often feel worse about their superior outcomes."

Figure 3: Study 6 Negotiated Outcome and Satisfaction Interaction for Sellers. (Source: Authors)

This last finding adds more nuance to the paper's overall story. Participants who lose an attractive alternative may do better at the bargaining table, but doing so is likely to leave them less satisfied with their results. Given that "satisfaction with a negotiated outcome is an important precursor of a negotiators’ engagement and success in future negotiations, the benefits of losing an alternative do come with a cost." In other words, because our satisfaction with past negotiations influences how we act in the future, the benefits a lost BATNA may confer could be diminished by sub-optimal actions in a future negotiation.

Conclusions

With their general hypothesis largely confirmed, the authors take some time to discuss why it is that lost BATNAs have such a strong impact on future negotiations. The answer has to do with the oft-cited concept of anchoring. Lost alternatives "serve as powerful anchors”, note the authors, "impacting negotiator aspirations, first offers, and ultimately the negotiated agreement." Indeed, the anchoring literature suggests that "once an alternative has been considered, it will still have some effect on the negotiation, even if it is ultimately lost." This is the case because "anchoring is a remarkably robust phenomenon that can persist even if the anchor is uninformative or irrelevant for the judgment at hand."

How exactly does anchoring work in the case of a lost BATNA? It works because a negotiator who has seen a good BATNA will seek “anchor-consistent” information that sheds a positive light on his bargaining position. In other words, once the BATNA is seen, new information is processed in such a way that reinforces the "correctness" of that now-lost offer. Indeed, the authors found in another of their experiments that forcing people to confront evidence showing the BATNA was incorrect can be an effective way to "de-anchor" during a negotiation. Barring that tactic, even alternatives that are lost and can no longer be attained powerfully influence how negotiators think about, prepare for, and ultimately act in negotiation settings.

This research has some practical implications for business managers. First, negotiators need to exercise care when generating alternatives prior to the start of a negotiation, given the impact that even lost options can have on negotiating strategies. Moreover, should anchoring begin to lead to unfavorable outcomes, negotiators should consider de-anchoring techniques as a way of counteracting possible negative effects.

Looking at the big picture, however, this paper comes to a positive conclusion. While losing a great job offer at the start of a job search is a shame, it may be of some comfort to know that just having seen it will probably lead to a better final outcome.

The Research

Garrett L. Brady, M. Ena Inesi and Thomas Mussweiler. The power of lost alternatives in negotiations. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 162 (2021) 59–80 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2020.10.010

Please take a second to rate this post.