The value of our digital footprints has just begun to be tapped — for better or worse

Research on consumer credit scoring using online profiling highlights the dramatic impact that our online markers may have in the near future

One of the widely-reported consequences of the pandemic has been the accelerated migration of consumer purchasing activity to the internet. Indeed, for many consumers around the world e-commerce is not a complement to traditional retail activity, it is a convenient substitute that has replaced traditional in-person buying. The ease of buying online is undeniable; however, this form of commerce has consequences that many consumers and even businesses do not fully comprehend. One such consequence is the set of markers that we create as we browse and shop online. Commonly referred to as our "digital footprint," the specific features of our digital presence, and what they say about us, are increasingly important topics for researchers and innovators.

A paper from Tobias Berg (Frankfurt), Valentin Burg (Home24), Ana Gombovic (Deloitte), and Manju Puri (Duke) provides a fascinating view into this emerging line of research. Their paper set out to understand whether a consumer's digital footprint can predict the creditworthiness of an online shopper as well as traditional credit-report databases. Their findings highlight just how much our digital footprint says about us and suggest that in the future everyday online activity may supersede traditional credit reporting with both positive and negative consequences for consumers.

As the authors note at the start of their paper:

Understanding the informativeness of digital footprints for consumer lending is significantly important. A key reason for the existence of financial intermediaries is their superior ability to access and process information relevant for screening and monitoring of borrowers. If digital footprints yield significant information about predicting defaults, then FinTech firms—with their superior ability to access and process digital footprints—can threaten the information advantage of financial intermediaries and thereby challenge financial intermediaries’ business models.

The Study

The authors based their research on data gathered from a German home furnishings retailer (similar to “Wayfair” in the United States) between October 2015 and December 2016. For any purchase over €100, the seller requires customers to create personal profiles before purchasing an item, and this profile is used to determine whether the buyer is allowed to buy “on invoice,” i.e., the merchandise is sent immediately and the customer has 14 days to pay the balance. In effect, the seller is giving creditworthy customers a short-term loan, the availability of which is determined by data drawn from two sources—two traditional credit reports and the buyer’s digital footprint. The first credit report provides basic information, such as whether the customer exists and whether the customer is currently in or has been recently in bankruptcy. The second credit report score draws on credit history data from various banks, sociodemographic data, and past payment behavior. For the purposes of their study, the authors labeled all customers for whom both reports existed as “scorable.”

The buyer’s digital footprint contains a variety of information collected from the buyer’s internet characteristics. Examples of information contained in the digital footprint include:

The device type (desktop, tablet, mobile) and operating system (e.g., Windows, iOS, Android)

The consumer’s e-mail provider (e.g., Gmx, Web, T-Online, Gmail, Yahoo, or Hotmail)

The channel through which the customer has visited the homepage of the seller, e.g, paid clicks (mainly through paid ads on Google), direct (a customer directly entering the URL of the E-commerce company in her browser), affiliate sites (customers coming from an affiliate site that links to the seller’s web page), and organic (a customer coming via the nonpaid results list of a search engine)

The hour of the day at which the purchase was made

Browsing time onsite

Other technical details

The authors collected data from approximately 270,399 purchases made by customers with low to very high creditworthiness (but excluding those with “very low” scores). These selection criteria, the authors note, have "the benefit of making our data set more comparable to a typical credit card, bank loan or peer-to-peer lending data set.” They also imply that “the discriminatory power of the variables in our data set is likely to be larger in a sample of the whole population compared to a sample that is selected based on creditworthiness.”

In the sample with credit bureau scores, the average purchase volume is €318 (approximately $350), and the mean customer age is 45.06 years. On average, 0.9% of customers default on their payment. Importantly, the authors’ data set is largely representative of the geographic distribution of the German population overall.

The Findings

Having collected the purchase data, the authors make some preliminary observations that inform their overall conclusions. The distinct features of the most commonly used e-mail providers in Germany allow the authors to infer information about a customer’s economic status,e.g., “T-online is a large internet service provider and is known to serve a more affluent clientele, given that it offers internet, telephone, and television plans and in-person customer support.” A customer obtains a T-online e-mail address only if she purchased a T-online package. Yahoo and Hotmail, in contrast, “are fully free and mostly outdated services.” Moreover, other research has shown that “owning an iOS device is one of the best predictors for being in the top quartile of the income distribution.” Thus, “based on these simple variables, the digital footprint provides easily accessible proxies of a person’s economic status absent of private information and difficult-to-collect income data.”

Interestingly, the authors believe that the digital footprint also provides information about a person’s character. “Her self-control,” for example, “is also reasonably assumed to be revealed by the time of day at which the customer makes the purchase (for instance, we find that customers purchasing between noon and 6 p.m. are approximately half as likely to default as customers purchasing from midnight to 6 a.m.).” Even the choice of e-mail addresses contains risk information. Eponymous customers—those who include their first and/or last names in their e-mail address—are less likely to default than those who include numbers. Even the way information is provided online is useful: typing errors or even lack of capitalization in names and addresses are associated with a higher credit risk level.

Looking at the data itself, some findings are as expected. The credit report information is a useful indicator of creditworthiness: “the default rate in the lowest credit score quintile is 2.12%, more than twice the average default rate of 0.94% and 5 times the default rate in the highest credit score quintile (0.39%).” Of more interest is that digital footprint variables also prove to be useful predictors of future payment behavior:

For example, orders from mobile phones (default rate 2.14%) are 3 times as likely to default as orders from desktops (default rate 0.74%) and two-and-a-half times as likely to default as orders from tablets (default rate 0.91%). Orders from the Android operating systems (default rate 1.79%) are almost twice as likely to default as orders from iOS systems (1.07%), consistent with the idea that consumers purchasing an iPhone are usually more affluent than consumers purchasing other smartphones. As expected, customers from a premium internet service (T-online, a service that mainly sells to affluent customers at higher prices but with better service) are significantly less likely to default (0.51% vs. the unconditional average of 0.94%). Customers from shrinking platforms like Hotmail (an old Microsoft service) and Yahoo exhibit default rates of 1.45% and 1.96%, almost twice the unconditional average.

As the authors expected, information about online behavior is also significantly related to default rates. Customers arriving on the homepage through paid ads, for example, “exhibit the largest default rate (1.11%),” perhaps because particular ads that are shown multiple times on various websites to a customer, “seduce customers to buy products they potentially cannot afford.” Customers being targeted via affiliate links, price comparison sites, and customers directly entering the URL of the seller, on the other hand, exhibit lower-than-average default rates (0.64% and 0.84%). Finally, “customers ordering during the night have a default rate of 1.97%, approximately twice the unconditional average.”

A few more findings are also worth noting. The first is that very few customers make typographical errors while writing their e-mail addresses (roughly 1% of all orders), but those who do are much more likely to default (5.09% vs. the unconditional mean of 0.94%). The second is that “customers with numbers in their e-mail addresses default more frequently, which is plausible given that fraud cases also have a higher incidence of numbers in their e-mail address.” Furthermore, customers who use only lowercase letters in their names and shipping addresses are more than twice as likely to default as those writing names and addresses with first capital letters.

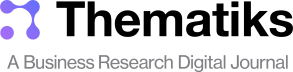

As one would expect (and as illustrated in Figure 1 below), the value of the digital footprint signals increase as they are connected:

When combining information from both variables (Operating system and E-mail host), default rates are even more dispersed. We observe the lowest default rate for Mac-users with a T-online e-mail address. The default rate for this combination is 0.36%, which is lower than the average default rate in the 1st decile of credit bureau scores. On the other extreme, Android users with a Yahoo e-mail address have an average default rate of 4.30%, significantly higher than the 2.69% default rate in the highest decile of credit bureau scores. These results suggest that even two simple variables from the digital footprint allow categorizing customers into default bins that match or exceed the variation in default rates from credit bureau deciles.

Figure 1: This figure shows default rates for combinations of the variables Operating system and E-mail host for all combinations that contain at least 1,000 observations. The x-axis shows default rates, and the y-axis illustrates whether the respective dot comes from a single digital footprint variable (e.g., “Android users”) or whether it comes from a combination of digital footprint variables (e.g., “Android + Hotmail”). (Source: Authors)

All in all, when compared to credit reports, a consumer’s digital footprint is both economically and statistically a better indicator of creditworthiness—not just at the time of purchase but with respect to recovery rates post-default. The authors are careful to point out that, in their opinion, digital footprint data is a complement, and not a replacement for, credit report data. Unfortunately, the authors do not expand on this conclusion sufficiently, given that they also claim that “even simple, easily accessible variables from the digital footprint are important for default prediction over and above [Italics mine] the information content of credit bureau scores.”

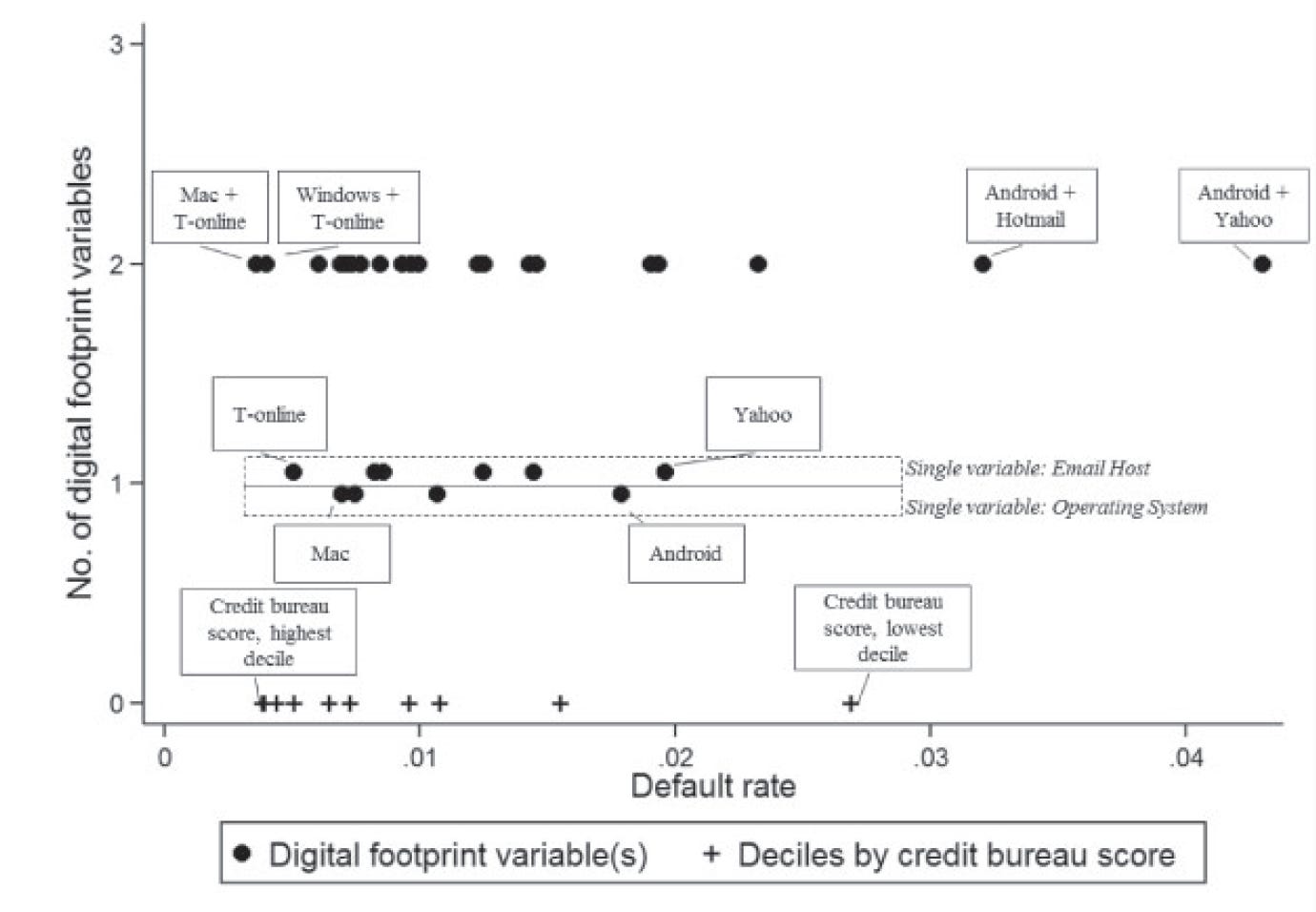

In their appendix, the authors provide additional anecdotal information that supports the conclusion that the findings of this study are not unique to this one seller. Taken together with the primary findings, all the evidence the authors present strongly suggests that digital footprints are a useful indicator of consumer behavior and may even indicate creditworthiness changes before they appear on credit reports. As illustrated in Figure 2 below, the addition of digital footprint data by the seller (which occurred in 2015) into credit decisions has had a material positive impact on the business: “introduction of the digital footprint decreases defaults by roughly one-third, yielding a decrease in default rates of approximately 0.8 percentage point or around €50,000 defaulted loans per month, equivalent to losses of €35,000 per month/0.6 percentage point with a loss given default of 70%.” Assuming a 5% operating margin, this change would be “an improvement in the operating margin of more than 10% that is attributable to the introduction of the digital footprint.”

Figure 2: This figure illustrates the development of default rates and number of observations around the introduction of the digital footprint. The vertical line indicates October 19, 2015, that is, the date of the introduction of digital footprints. (Source: Authors)

Conclusions

In a paper with many provocative points, perhaps the most arresting is the authors’ analysis of the usefulness of digital footprint in assessing the creditworthiness of consumers who are “unscorable” because they have little or no credit history. The authors conclude that “the discriminatory power for unscorable customers matches the discriminatory power for scorable customers.” In other words, digital footprint data can be used to analyze correctly the creditworthiness of consumers with little or no credit history. If this conclusion is correct, it has an important implication:

Given the widespread adaption of smartphones and corresponding digital footprints, the use of digital footprints thus has the potential to boost access to credit for some of the currently 2 billion working-age adults worldwide who lack access to services in the formal financial sector, thereby fostering financial inclusion and lowering inequality.

The authors note that their conclusion is an innovation path that some companies in the FinTech space are already following. These startups, the authors note, “have the vision to give billions of unbanked people access to credit when credit bureaus scores do not exist, thereby fostering financial inclusion and lowering inequality.” This paper’s findings clearly support that overall vision, for they suggest a deep well of information value may indeed lie untapped.

In closing their paper, the authors refer to something known as the Lucas critique, which argues that individual actors consider potential policy changes in their behavior, i.e., that the relationship between people and policies is dynamic, and that one cannot analyze the impact on the relationships between people and policy without first understanding the forces that shape people's daily behavior. This critique is relevant, for if digital footprints were to become widely used indicators of creditworthiness then people might alter their online behavior to leave a better footprint—something much easier to do than to alter the payment behavior that generally shapes credit report scores. Thus, the authors note that the digital footprint “might evolve as the digital equivalent of the expensive suit that people wore before visiting a bank.” Of course, this kind of change is easier said than done, and it may turn out to be difficult to change one’s digital footprint than one might imagine. Moreover, should digital footprints become more important in credit decisions, it is likely that regulators would take a greater interest in them, which could also alter their value.

Reflecting on this paper, we recalled a conversation with the Chief Innovation Officer of a global technology services firm a few years ago. The subject of our discussion was data privacy, and he explained to us that the internal debate his firm was having not just about defining what could be done with the data they collected then but what might be possible in the future. His comments are worth quoting:

Imagine that in 2018, as part of a cellphone warranty registration process, we ask for your favorite color. Without much concern, you casually answer “orange.” Now imagine that in 2023, our analytics team figures out that people who like orange are significantly more likely to submit fraudulent warranty claims, so we decide you can’t buy an extended warranty on your new phone in 2024. Now imagine that law enforcement agencies conclude that people who like orange are more likely to commit other crimes as well and ask for our list of orange-loving customers. What worries me is not what we can do with all your personal information today but what we—or others—might be able to do with it years from now. That’s something we can neither predict nor write into any consumer agreement at the moment.

Considering all the information about us that digital footprints may contain, it strikes us that so many digital markers we leave behind us may seem inconsequential and ephemeral. The reality, however, may be very different. On the one hand, one can imagine digital footprints, as the authors suggest, expanding banking access to young people, immigrants, the working poor, and other populations traditionally left out of the formal banking system. On the other hand, one can imagine digital footprints being used as invisible credit reports: decision support systems about which consumers have no power or even knowledge. Either, or both, futures may soon be possible.

The internet never forgets, someone once said. As this paper shows, the reality is much more complex than that. The internet not only never forgets, it is also constantly learning. As it does, it continuously finds new value in old data. What was of little value yesterday may turn out to be priceless tomorrow. Moreover, as this paper well illustrates, we exist in both physical and digital forms. As researchers and innovators continue their relentless push forward, it is the digital form that may prove to be the more powerful.

The Research

Tobias Berg, Valentin Burg, Ana Gombović, Manju Puri, On the Rise of FinTechs: Credit Scoring Using Digital Footprints, The Review of Financial Studies, Volume 33, Issue 7, July 2020, Pages 2845–2897, https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhz099