Youthfuls, Matures, and Veterans: Understanding subjective age in late-career employees

Novel research begins to look at how late-career employees see themselves and their abilities at work — an important topic as more older workers remain on the job

One of the major demographic trends in the U.S. (and in other developed nations) is that people are living longer. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the life expectancy of the average person in America has increased from 76.8 years in 2000 to 78.7 years in 2018. As shown in Figure 1 below, the percentage of people 55 and over in the labor force has more than doubled since the 1990s, with about 37 million older Americans in the workforce as of March 2021. With so many people choosing to work longer, companies will have to manage more older workers in the years to come, a situation that poses an interesting question: is chronological age a good indicator of someone's work capacity? In other words, do older workers show similar traits at a given age point, or is chronological age perhaps not a fully accurate indicator of what someone can contribute in the later stages of a career?

Figure 1: Americans age 55 and over in the labor force (Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics via FRED)

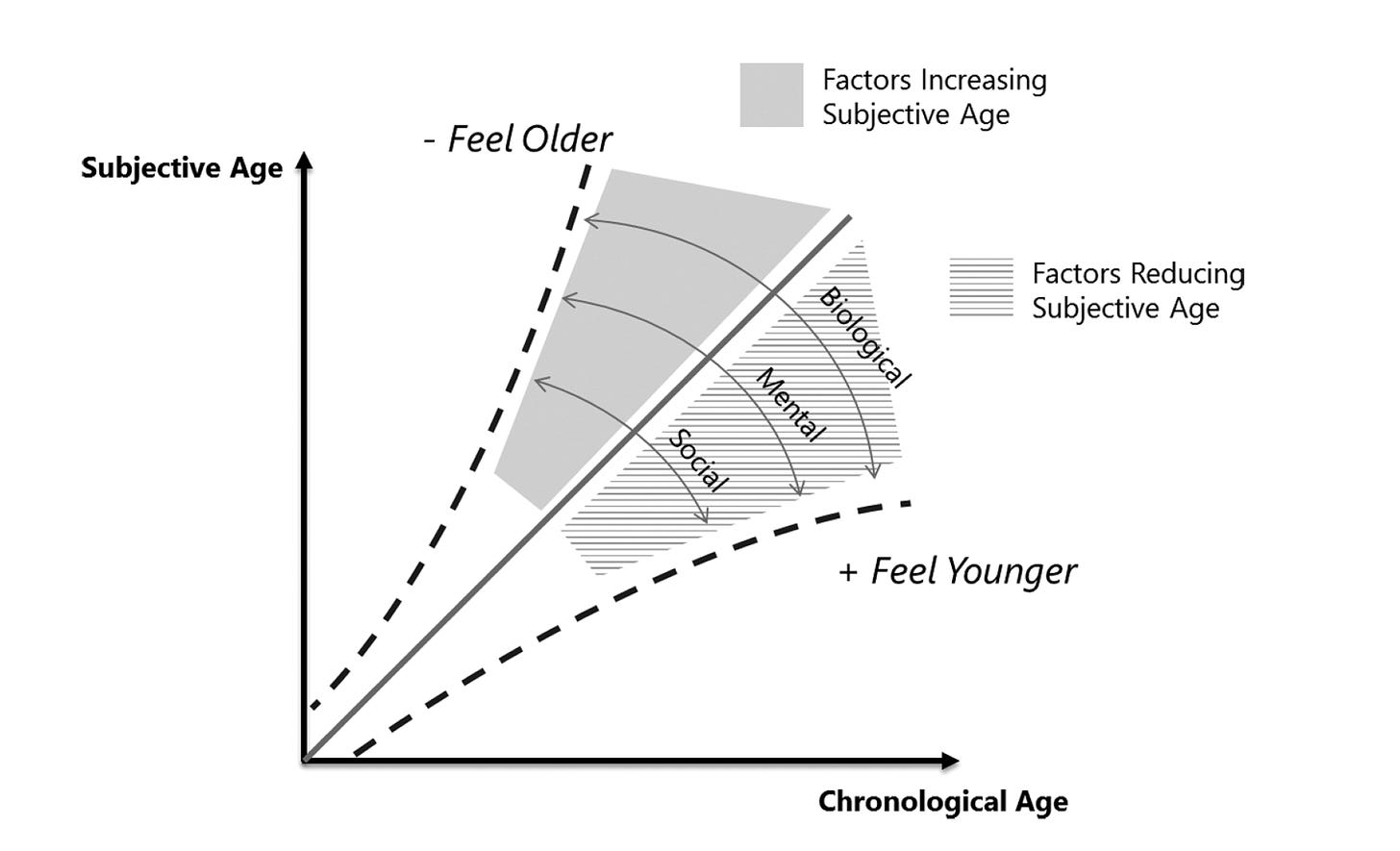

In a recent paper, researchers Noemi Nagy (South Florida), Ulrike Fasbender (JLU Giessen), and Michael S. North (NYU) provide some provocative answers to the questions noted above. Their research focuses on a concept called subjective age, a term with a long history as well as varying meanings depending on its research context. Generally, as shown in Figure 1 below, the term refers to a comprehensive representation of the various ways in which a person experiences the aging process, i.e., whether the “felt” age of people is at, above, or below their chronological age.

Figure 2: Subjective age and chronological age model (Source)

As the researchers point out early on, subjective age has real-world implications. For example, research has shown that feeling younger than one's chronological age predicts various outcomes, many of them adaptive, among older adults, e.g., individuals who feel younger than their age tend to take better care of their bodies and are more likely to observe preventive health behaviors. For this reason, stratification of older customers based on their subjective age is common in marketing and consumer research. Indeed, note the authors, "as early as the 1980s, research has found that older people identifying as younger than their age group belong to a younger target market, despite their chronological age."

The authors further note that while some critical voices have challenged the concept of the subjective age, there has been growing academic interest in subjective age at the workplace, as researchers have used the concept to look at issues such as retirement preferences, goal commitment, work motivation, etc.

To examine subjective age in older workers in this specific study, the authors employ what is known in psychology research as the person-centered approach. Technically speaking, this method assumes "both inter-individual differences—that is, not assuming homogeneity among the population—as well as intra-individual variation in the interplay between different underlying factors." Stated simply, the person-centered approach examines people rather than populations and assumes that factors that may be common within a group may operate differently at the individual level.

One other point to note is that subjective age is something experienced by younger workers, as well, though it tends to vary more later in life — more on that point later.

The Study

The authors had a few goals in mind for their effort:

They wanted to evaluate the various ways of assessing subjective age used in previous research.

They wanted to understand how attributes such as health, workability, and self-perceptions impact subjective age.

They wanted to understand the relationship between subjective age and at-work attributes, such as work and organizational engagement.

The findings presented in the paper are based on extensive surveys of 229 German workers. All participants were active in the workforce in their late-career phase (i.e., above age 50), and there was equal distribution between male and female participants. Respondents came from a large variety of industry sectors and occupations, with organizational tenures ranging from less than a year (4.2%) to more than 25 years (32.9%), with the majority of participants (13.9%) working in their current organization for 5–10 years. The educational level of the participants was "representative of the working population in Germany and ranged from no vocational training (2.1%) to postgraduate education (11.8%)."

For all participants, the authors measured an extensive variety of criteria (twenty separate dimensions in total) that included chronological age, subjective age, relative subjective age (i.e., the chronological age of the respondents when examining subjective age), work engagement, as well organizational citizenship behavior(OCB), which encapsulates positive actions and behaviors employees show at work, e.g., civic virtue, altruism, etc., that are not part of their inherent job roles.

The Findings

From their research, the authors distinguished three broad profiles of late-career workers:

Youthfuls: employees who feel much younger than their chronological age

Matures: employees who feel somewhat younger than their chronological age

Veterans: employees who feel older than their chronological age

Based on participants’ responses, the researchers determined that youthfuls felt on average 11 years younger than their chronological age, matures felt 6 years younger than their chronological age, and veterans felt 3 years older than their chronological age. Youthfuls were more likely to be male (54%), while veterans were more likely to be female (60%). There was no gender difference for matures.

At work, youthfuls "reported significantly higher values of work engagement and taking charge in comparison to participants belonging to the other two profiles." Matures also see themselves as productive and motivated at work, just to a lesser degree than youthfuls. Veterans, however, reported the lowest levels of motivation and engagement. These latter employees are the ones most likely to need some support at work, e.g., help with their workloads, more flexible scheduling, or stress reduction support. It is critical to note, however, that there was no "significant difference between the groups in terms of in-role behavior, indicating that all participants of our study report fulfilling their work responsibilities, irrespective of their subjective age profile."

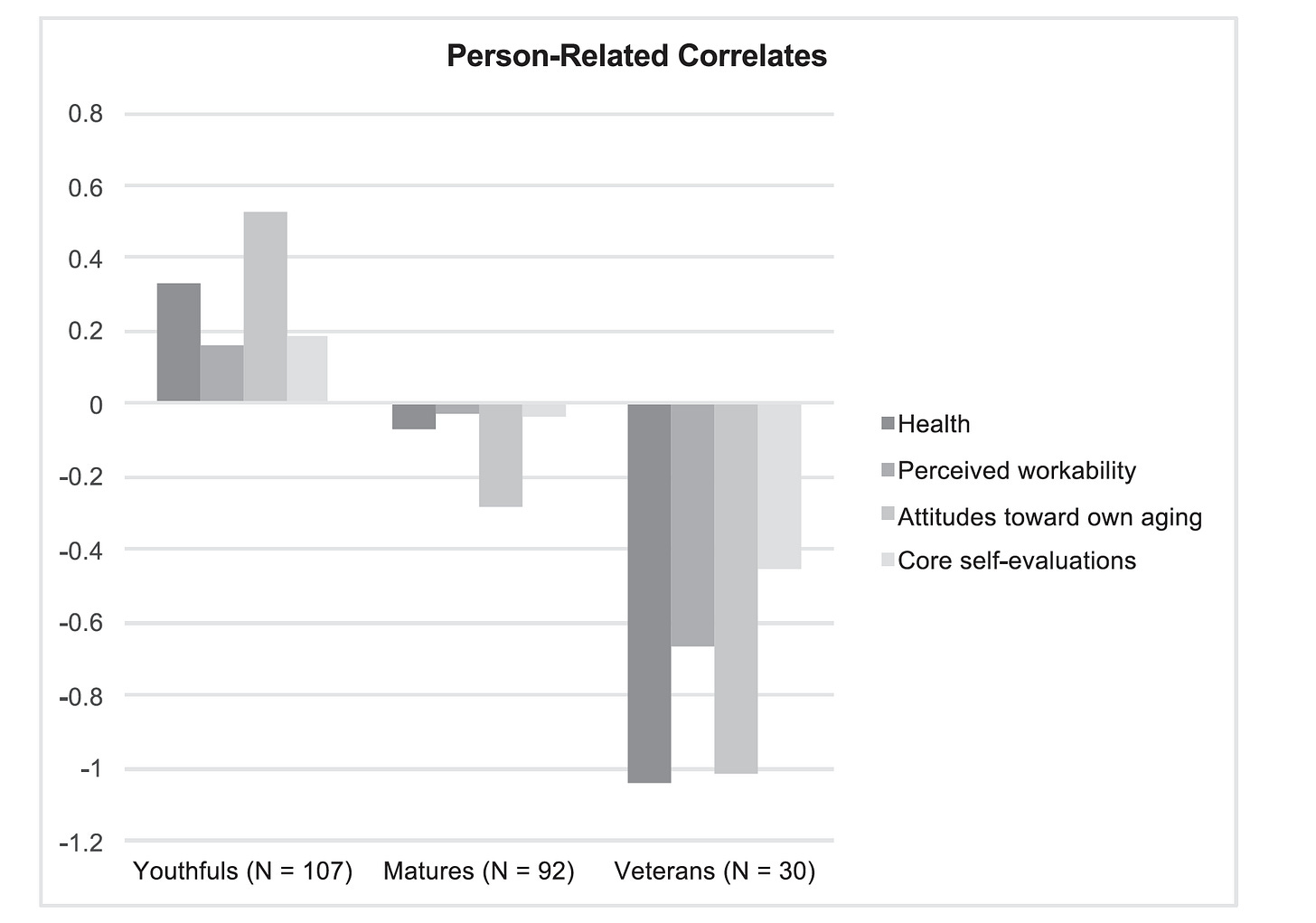

Figure 3: Health, perceived workability, core self-evaluations, and attitudes toward own aging were significantly higher in Youthfuls than in other profiles (Source: Authors)

As shown in Figure 2, an important finding was that physical health, perceived workability, core self-evaluations, and attitudes toward aging significantly predicted profile membership. Youthfuls, note the authors, "reported to be in good health, have high levels of perceived workability, positive core self-evaluations, and positive attitudes toward own aging." In contrast, "matures had below-average levels on all indicators and veterans had levels far below average, signaling poor health, low perceived workability, negative core self-evaluations, as well as negative attitudes toward own aging."

With regards to civic virtue and altruism, a large gap emerged between youthfuls and matures only. As the authors note:

Our results show that subjective age profiles differentiate between central work-relevant outcomes and highlight how employees with comparable chronological ages show disparate levels of work engagement and OCB, to some extent related to their subjective ages. Although we cannot rule out any confounding variables in the relationship between subjective age and the investigated work outcomes, we can confirm that a younger subjective age was significantly related to higher levels of work engagement and OCB in our investigated sample.

As a result of their findings, the authors suggest that youthfuls can be considered the most "useful" older employees. For example, "youthfuls are particularly fitted for leadership positions, because highly engaged employees typically show higher levels of effective leadership behaviors, such as transformational leadership or leader-member exchange."

It is clear from the findings that a youthful's physical health and their perceptions of aging have much to do with subjective age and form a virtuous circle. Older workers with good health generally try to preserve it, leading to more positive views of the aging process and more willingness to lead and engage at work. Of course, note the authors, an aging workforce means that organizations must accommodate all types of late-career workers, including matures and veterans. Consequently, it may behoove organizations to implement programs that support the health of older workers, especially those in leadership roles. In addition, "organizations can also support more favorable attitudes toward own-aging by creating an age-friendly climate and implementing age-inclusive human resources strategies." Together, these practices can help organizations deal with and support the different subjective aging profiles and thus derive the best outcomes for both company and workers.

Conclusions

This study is the first to label different subjective age profiles in late-career employees. As such, there are many issues it does not address. For example, it does not look at subjective age in middle-career or early-career workers. Indeed, early-career workers are often labeled as behaving “younger” or “older” than their chronological age, so it is likely this is a phenomenon that could be looked at across workers’ entire lifespan. Moreover, the study does not examine how forces operating inside and outside the workplace affect subjective aging. For example, subjective age might be affected by the way in which younger colleagues treat an older worker or by the demographics of a company's senior leaders. The study also omits any analysis of the biological or psychological factors that may affect subjective age. For example, one recent Korean study noted that when older people incorrectly over-estimate their loss of cognitive skills, they tend to perceive themselves as older than their chronological age.

The authors themselves document the study's omissions, but these tactical limitations should not deter leaders from understanding the strategic picture the research presents. The authors have done older workers a favor in presenting a good case for a more nuanced view of their age perceptions, psychological dimensions, and evolving capabilities. It would be a positive sign to see corporate support for this previously neglected line of research in the future for two important reasons. First, as shown in Figure 4 below, recent research estimates that the U.S. “missed out on a potential $850 billion in GDP in 2018 (an uplift of more than 4%) because those age 50-plus who wished to remain in or re-enter the labor force, switch jobs or be promoted within their existing company were not given that opportunity.” That loss is projected to grow to $3.9 trillion in 2050. More research into issues such as subjective age might eliminate wrong views about older workers (and consumers), a positive development for companies, workers, and the economy as a whole.

Figure 4: Potential cost of labor age discrimination on GDP in 2018, by industry ($ billion) (Source: AARP/The Economist Intelligence Unit)

Second, a fundamental imperative of corporate life in 2021 is the need to look beyond traditional human stereotypes of individuals' cognitive and social realities. Older workers, many of whom are entrusted with the highest levels of corporate leadership and responsibility, deserve the same level of understanding as their younger colleagues. As two of the paper’s authors note in a recent article, "businesses can help not only by understanding that the labor force is rapidly aging, but also by recognizing that chronological age alone is an imprecise indicator of work motivation and performance." Indeed, organizations that recognize and tap into the diversity of the coming aging workforce will be the ones who benefit the most.

The Research

Noemi Nagy, Ulrike Fasbender, Michael S North, Youthfuls, Matures, and Veterans: Subtyping Subjective Age in Late-Career Employees, Work, Aging and Retirement, Volume 5, Issue 4, October 2019, Pages 307–322, https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/waz015