Climbing the two ladders: how Chinese companies move up the global value chain

An innovative model explains how Chinese companies catch up to and even surpass their Western competitors and the markets in which they are more likely to excel

Competition with Chinese companies — in global markets as well as in China — is one of the defining facts of life for many companies around the world. In a variety of markets and industries, Chinese brands continue to evolve upwards and outwards, often meeting or surpassing the performance of Western incumbents. As an MIT Tech Review article noted about competition within China:

In China’s ice cream market, Unilever and Nestlé S.A. had won market shares of only 7% and 5%, respectively, by 2013 — despite decades of investment. The market is dominated by two companies that most people outside of China have probably never heard of: China Mengniu Dairy Co. Ltd., with a 14% market share, and Inner Mongolia Yili Industrial Group Co. Ltd., with 19%. Meanwhile, in the Chinese market for laundry detergent, Procter & Gamble was the leading foreign brand, with an 11% share in 2013, but it was overshadowed by two China-based companies: Nice Group Co. Ltd., with more than 16% of the market, and Guangzhou Liby Enterprise Group Co. Ltd., with 15%. The home appliance market is similarly structured. Chinese companies dominate the market, with Haier Group at 29%, followed by Midea Group (12%) and Guangdong Galanz Group Co., Ltd. (4%). The two top multinational competitors, Germany’s Robert Bosch GmbH and Japan’s Sanyo Electric Co. Ltd., have only niche positions (each with less than 4%). Competition with Chinese companies — in global markets as well as in China — is one of the defining facts of life for many companies around the world. In a variety of markets and industries, Chinese brands continue to evolve upwards and outwards, often meeting or surpassing the performance of Western incumbents.

Indeed, Chinese companies such as Huawei (telecommunications equipment and smartphones), Lenovo (PCs and servers), Haier (home appliances), Galanz (microwave ovens), DJI (commercial drones), BGI (gene sequencing), CRRC Corporation (high-speed rail), Pearl River (pianos), and ZPMC (port machinery) have even managed to outperform their multinational rivals not just in China but also in external markets.

Despite the success stories, the evolution of Chinese corporate competitiveness is not evenly distributed. In some industries, Chinese companies have done very well; yet in other sectors, they have struggled against foreign competitors at home and abroad. Given the variety in outcomes, an important strategic question is what factors determine whether a Chinese brand is more or less likely to equal or surpass foreign incumbents. A paper from Peter J. Williamson (Cambridge Judge), Bin Guo (Zhejiang), and Eden Yin (Cambridge Judge) provides a useful model for considering this question.

The Two Ladder Model

At the very start of their paper, the authors suggest that two strategic factors determine the likelihood of Chinese competitiveness. The first factor is the degree to which a sector’s local demand is fragmented, i.e., is the Chinese version of the sector contiguous, forming a “smooth path” from low to high end, or is it uneven as a rocky path climbed in leaps of various lengths. The second factor is the capability progression required to move up the sector’s value chain. Again, is there a clearly defined capability path for a Chinese company to ascend, or are there big technology leaps required along the way? The authors see these two dimensions as “ladders” — market and capability, respectively — that Chinese companies must climb in order to attain global competitiveness. Understanding these ladders, the authors argue, is a useful way to assess whether a Western incumbent faces a higher or lower risk of being disrupted by a Chinese competitor.

Ladder 1: Demand

For the authors, the market ladder is characterized by three dimensions: “relative segment size, increments between relative segments, and the continuity between adjacent segments.”

Segment size is important because Chinese companies typically need a “wide first step” in order to start their climb. The lowest-end segment, the authors note, “often acts as an important stepping stone Chinese companies can use to establish themselves in a market initially.” Because the product functionality in this segment is relatively basic, “the quality and depth of capabilities required to compete in this segment are limited.” Competitive rivalry tends to “be waged on price, enabling local firms, often from rural areas, to leverage their access to very low-cost labor.”

Increment size is important because Chinese companies find it easier to move up in a market where demand has many levels, i.e., it is easier to “step up” from one demand class to another if there are narrow segments. As the authors note, “a ladder with closely spaced rungs will enable Chinese competitors that enter at the low end to gradually climb up to higher-end segments without the need to understand a radically different set of customers or buying behaviors.” Rather than having to serve complex customers from the start, “they can succeed in moving up-market by serving successively more demanding customers who, while they have higher expectations of the product or service, do not have fundamentally different buying criteria.”

A ladder that has widely spaced rungs is much harder to climb. A case in point is the Chinese business software industry. The authors explain that local players Yonyou and Kingdee “have been able to dominate the segment made up of small- and medium-sized enterprises, which require localized features, simple installation, and low prices.” But the huge gap between this segment and large enterprises “means that foreign companies such as Oracle and SAP remain the leading players in the top-end enterprise resource planning software.”

As for segment continuity, markets with no large gaps are easier to ascend. When one or more segments are missing, progress becomes more difficult because any company wishing to move from the low to high end “has to leap across the missing segment.” The domestic motorcycle sector is a good example of this phenomenon:

Some 95% of the market was in the lower end segment of motorcycles with between 50 and 150 cubic centimeters (cc) of engine displacement (as a measure of power). There was a small but valuable upper-end segment of powerful motorcycles with greater than 250 cc engines that accounted for around 3% of the market. This was dominated by Japanese firms such as Honda and Yamaha. But the mid-market segment of 150 cc motorcycles, the largest segment in most countries, was almost entirely missing in China, accounting for just 1.8% of the total market...As a result of this segment discontinuity, Chinese motorcycle manufacturers had neither the incentive nor the opportunity to gain experience in upgrading their products to serve the tiny mid-market segment. At the same time, the leap of understanding and capability required to compete with their Japanese rivals presented an almost impossible challenge. As a result, Chinese companies failed to catch up with their international competitors in the motorcycle market. They have still not done so today.

Naturally, the three dimensions are not static. Forces such as changing company ownership, strategic direction, and technological shifts such as e-commerce are continuously reshaping the market ladder. Indeed, in today’s China, “two of the most important factors reshaping China’s market ladders are the rise of a huge middle class and the boom in e-commerce, particularly the use of smartphones.”

Ladder 2: Capability

The second ladder refers to the fact that “companies usually catch up by first developing or accessing simpler technologies that allow them to compete at the lower end of the market.” As they enhance their skills and abilities, they attempt to serve more complex markets. As with market ladders, three factors shape capability ladders:

Length: “the existence of simpler technologies that are relatively easy to master and are suitable to meet the needs of lower-end market segments (parallel to the existence of sizeable demand for low-end products and services in the market ladder);”

Increments: “the evaluation of the difficulty and complexity between different rungs of the capability ladder;” and

Continuity: “which looks at whether or not there are gaps or discontinuities in the capability ladder.”

Relative to the first dimension, the authors note that the longer a ladder is — the more it spans a wide range of technologies, from simple solutions to complex, sophisticated ones — the easier it is for Chinese companies to climb. For example, in the Chinese market for “digital direct radiography machines, the availability of simpler line-scanning technologies that were easy to master and suitable for basic applications such as chest X-rays allowed Chinese competitors such as Zhongxing Medical to build an initial base of capabilities.” Over time, the company eventually mastered “the flat-panel X-ray imaging technologies pioneered by Koninklijke Philips N.V (Philips) and General Electric, which are capable of creating videos of a patient’s beating heart.” On the other hand, in the passenger jet industry’s truncated ladder, “Chinese companies such as the Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China (Comac) could not enter by adopting a simpler technology and gradually climbing the capability ladder.” Instead, “Comac was forced to embark on the decade-long, difficult process of mastering state-of-the-art technologies before it could enter the market.”

The jet case also illustrates the important role played by “the size of the increments in difficulty and complexity between different rungs of the capability ladder.” Comac’s affiliate, Harbin Aircraft Industry Group, has been selling turboprop aircraft to customers since 1985. However, the large gap between turboprop technology and the technology needed for passenger jet aircraft meant that its C919 passenger jet entered service for the first time in 2021.

As with the market ladder, continuity refers to a ladder made up of smooth or disjointed increments. For example, note the authors, mobile phone sophistication is defined by “a series of more powerful chipsets, better lenses and cameras, antennas, microphones, speakers, and more powerful software.” This smooth ladder “has enabled many Chinese firms ranging from Huawei, Lenovo, and Xiaomi through to Shanzai players such as SciPhone — to upgrade the quality and features of their products rapidly through a fast-paced series of incremental improvements to match world standards and sometimes achieve leadership.” In contrast, the passenger elevator business “exhibits significant discontinuities between, for example, the high-speed hydraulic elevator technology delivering speeds of 2.5 meters per second used in taller buildings and the traction technology that can be used in less demanding, low-rise applications.” Consequently, it has been difficult for Chinese competitors to climb the capability ladder and the high-end segments in the Chinese elevator market are still dominated by foreign companies, “including Otis, Mitsubishi Electric, Schindler, and Kone, who together enjoy over 70% share despite China being the world’s largest market and with local companies in the market for several decades.”

Other factors

In addition to ladder characteristics, the researchers note, certain other factors impact the success a Chinese company has moving up the capability ladder. For example, Chinese companies ascend more rapidly when there is wider availability of external knowledge about a sector. The government’s regulatory position is also important, though sometimes not in the ways intended. For example, note the authors, while government policies requiring joint ventures helped Chinese train manufacturers to become globally competitive, they had the opposite effect in the car industry where VW and Toyota remain the dominant players.

Another key factor is the structure of the global value chain itself. In industries such as car manufacturing, Chinese companies entered as relatively low-level suppliers and then moved up the global value chain. For example, Wanxiang Group, today a tier-one supplier to the global automobile industry, first entered the automotive value chain as a supplier of universal joints. However, “Wanxiang was gradually able to understand higher value-added technologies and the components in which they were embedded.” As it climbed the capability ladder, “Wanxiang expanded its product range to include complete steering systems, driveshafts, and braking systems.” In contrast, “flow” industries, such as petrochemicals have been difficult for Chinese companies because these sectors require “a chain of highly systemic interactions between research, development, and clinical testing teams working together to use their tacit knowledge of interrelated, often proprietary processes.”

Figure 1: Determinants of when Chinese competitors can catch up (Source: Authors)

As expected, acquisition opportunities represent another way “through which Chinese companies can access external technological know-how to help them climb the ladder.” Wanxiang, in fact, used acquisitions to climb the technological ladder. It made “its first overseas acquisition in 2001 with the purchase of a controlling interest in Universal Automotive Industries (UAI), a Nasdaq-listed U.S. supplier of braking systems.” Over the next 15 years, it acquired more than 30 companies, and “each of these [acquisitions] brought access to new technologies, helping Wanxiang climb the capability ladder.”

Competitive Responses

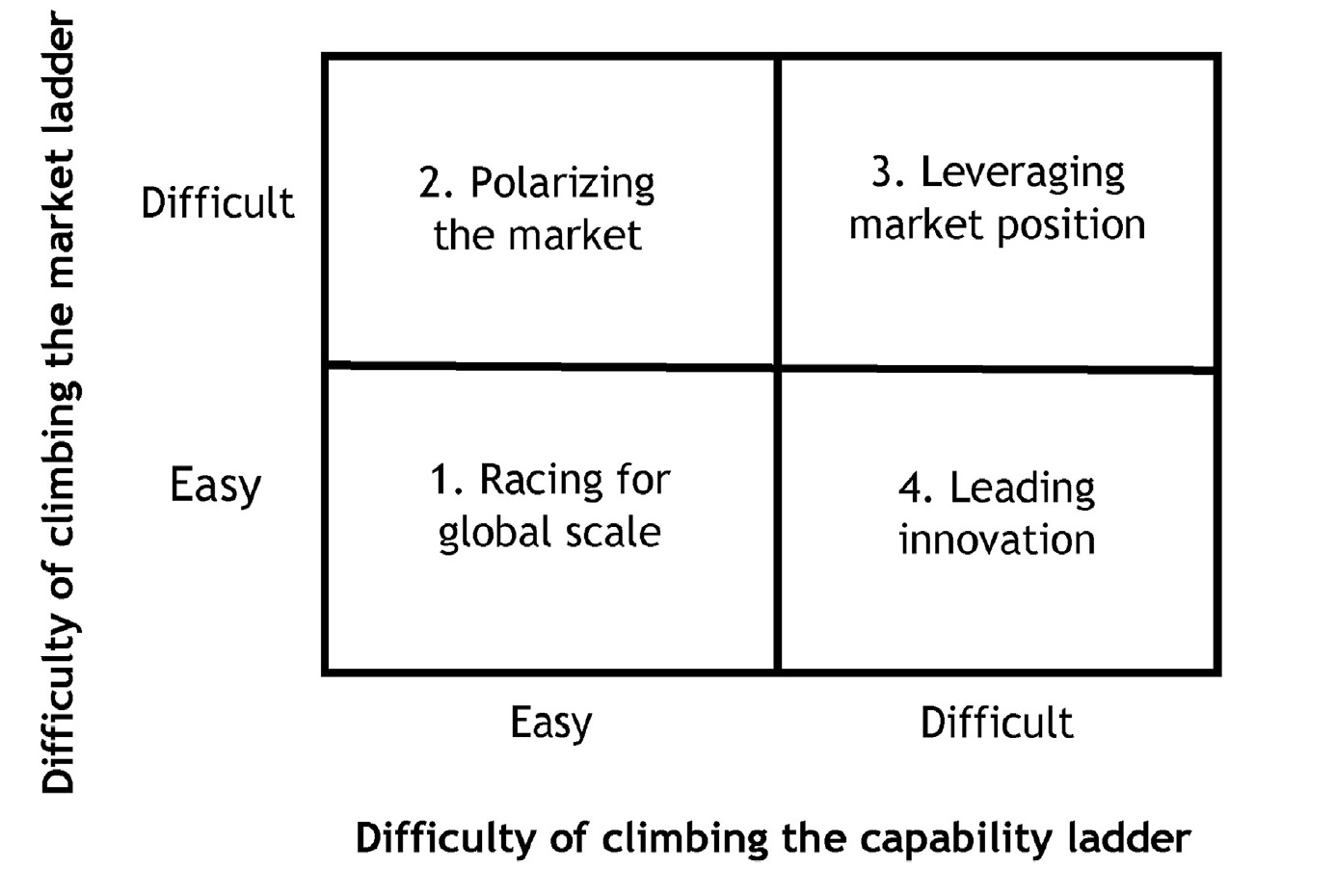

In the final sections of their paper, the authors summarize their model graphically. The authors explain that “by analyzing the characteristics of the respective market and capability ladders for their industry, companies faced with growing Chinese competition can first assess their level of vulnerability and then develop appropriate strategies to counter this competitive threat.” Depending on the nature of the market and capability ladders, four scenarios are possible as depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Assessing vulnerability to Chinese competition (Source: Authors)

The authors explain the figure thus:

Scenarios 1 and 3 are straightforward: market and capability ladders with characteristics that make it relatively easy for Chinese competitors to climb, increase vulnerability, and characteristics that impede Chinese competitors trying to climb the ladder reduce vulnerability. Given the nature of their market and capability ladders, some of the industries prone to Scenario 1 include personal computers, smartphones, and other consumer electronics as well as home appliances...Scenario 3 includes aerospace, banking, branded luxury goods, and possibly semiconductors.

Scenario 2 is more complex. It is relatively easy for Chinese competitors to climb the capability ladder, but they face impediments in climbing the market ladder and, thus, they are likely to try to win share by disrupting existing market segments. A common strategy to achieve this involves rapidly deploying new technologies into the mass market, gaining scale advantages that undermine the price premium incumbents enjoy in up-market segments. Industries that have begun to see this scenario play out include medical equipment, machinery, and renewable energy equipment such as wind turbines and solar panels.

In Scenario 4, it is relatively easy to climb the market ladder, but not to match the quality of high-end technology. The risk here is that Chinese competitors reverse-engineer the offering to eliminate features most customers do not often use and deploy adequate but cheaper and simpler technologies to offer improved value-for-money, commoditizing the market and forcing rivals to compete on cost. A classic example is the revolution Haier initiated in the market for specialist wine-storage refrigerators as well as those used in commercial bars and restaurants.

Figure 3: Strategies to respond to Chinese competition (Source: Authors)

As shown in Figure 3, the authors also provide recommended strategies that can be applied to each of these scenarios. Space does not allow a summary of them all, but one of the more interesting ones is “polarization.” In this scenario, a Western incumbent disrupted by a Chinese product that is inferior on some dimensions but delivers the key attributes that most customers value, responds by emphasizing the non-technical attributes of its products. Tesla, note the authors, “recently embarked on this path in China, emphasizing its Californian roots, promoting its styling and driving experience, and enhancing the comfort of its rear seats to appeal to wealthy Chinese who typically employ a chauffeur.”

Conclusions

In their final discussion, the authors rightly note that “predicting the industries in which fast-rising Chinese companies will be able to catch up with their incumbent multinational competitors and when is not an exact science.” But the framework they present for Western executives “can provide an important first step toward a reliable guide.” As noted above, the “guide” function comes down to three strategic assessments of a market:

The relative size of different segments from low end to high end;

The size of the quality increments between these segments; and

Continuity, which looks at whether or not there are gaps in the segments of this market ladder that could trip Chinese companies up.

Likewise, Western executives should understand the capability ladder that Chinese companies are climbing, determining whenever possible:

The length of the capability ladder;

The size of the increments in capabilities necessary to move from one technology to the next; and

Whether or not there are missing links between technologies that are difficult to leapfrog.

Wherever the results of these assessments ultimately land, the researchers advise, “it is important to remember that whatever else Chinese companies are doing, they are certainly not standing still.” This is a challenging statement, of course. Still, the model presented in this paper offers a novel and helpful framework for Western strategists to understand the progression of Chinese competitors in their markets and develop the appropriate strategic responses.

The Research

Peter J. Williamson, Bin Guo, Eden Yin. When can Chinese competitors catch up? Market and capability ladders and their implications for multinationals. Business Horizons, Volume 64, Issue 2, 2021, Pages 223-237, ISSN 0007-6813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2020.11.007.