Employee burnout is the pandemic's invisible workplace legacy

The pandemic did not create burnout, but new research shows that it made an already bad problem worse — a condition that will continue even after the crisis is over

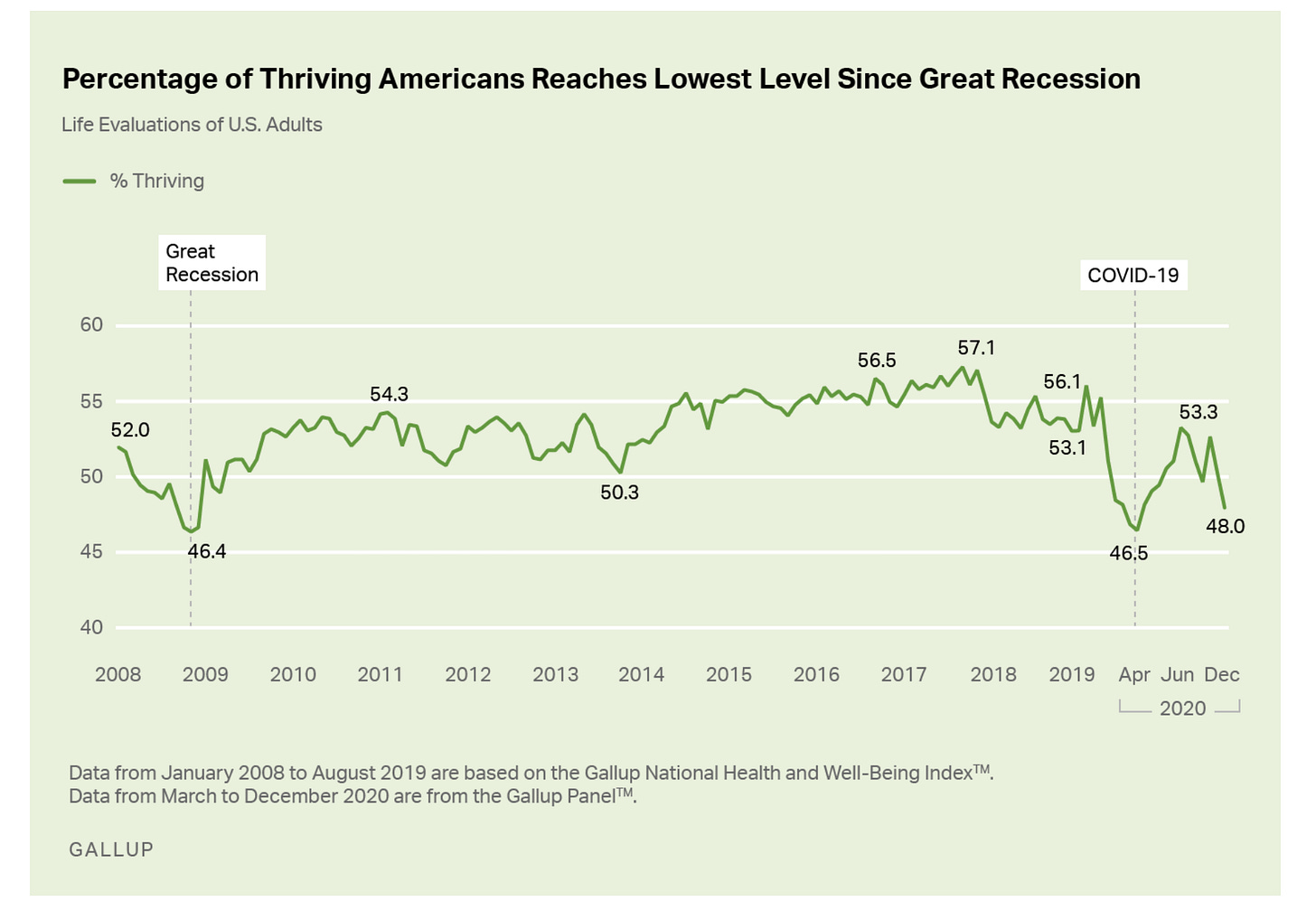

When one thinks of employee engagement with work and of employee well-being, it is natural to think of them as positively related. It makes intuitive sense to think that the better people feel about their lives, the more likely they are to feel engaged professionally. This connection is exactly what a long-running employee survey managed by the Gallup organization has shown since the survey’s inception in 2009. In 2020, however, the survey’s latest results for the first time showed a disconnect between engagement and well-being, and this divergence may suggest a larger problem that companies need to address as the pandemic comes to a close.

2020: Wellbeing and engagement diverge

As noted above, throughout the survey’s history, employee engagement and well-being have been reciprocal, i.e., “each influences the future state of the other.” But they are also additive, notes Gallup, as “each makes a unique but complementary contribution to the thoughts, feelings, behaviors, and performance outcomes of employees.” In 2020, the two dimensions disconnected, with well-being lowering dramatically even as engagement stayed high. As the Gallup authors note:

People across the nation have experienced a significant decline in personal wellbeing due to COVID-19. Negative emotions, like stress and worry, spiked during the early months of the pandemic and sustained high levels continued to drain Americans' emotional fortitude. Even worse, Americans' life evaluations hit their lowest levels since the Great Recession of 2008 with only 46.5% of individuals evaluating their lives as "thriving" in April of 2020 -- a 15% drop from pre-pandemic levels. Common sources of pandemic-induced distress run the gamut from health and job concerns to social disconnectedness, social injustice, childcare strains, and uncertainty about the future.

Interestingly, stress and worry were worse for remote workers than on-site workers amid COVID-19 and were consistent regardless of whether workers were married or single, with or without children. Indeed, the authors note that “unmarried, fully remote workers are particularly susceptible to feelings of loneliness and isolation.”

Given the fall in feelings of well-being, the researchers were surprised to find that employee engagement “reached a new record high multiple times throughout the summer before cooling off the rest of the year, and it closed at one percentage point higher than the 2019 average.” The survey also notes increased volatility in 2020. For example, engagement spiked “to an all-time high in May before it dropped dramatically immediately after the killing of George Floyd and the ensuing social justice protests.” Then, weeks later, “June engagement ascended back up to a new record high with 40% of employees engaged in their jobs.” This engagement volatility suggests that “we are navigating a constant state of new challenges while grappling with unknowns about the future.”

At the macro level, the Gallup survey shows a workforce that made great efforts to stay connected to work, even as their personal well-being decreased. This conclusion is in line with other recent research that indicates workers have worked longer hours just to keep up with pre-pandemic levels of output. It is no surprise, therefore, to see the Gallup authors conclude that “our biggest concern is that many employees have hit or are approaching a breaking point that leads to burnout and suffering with long-term consequences.” Indeed, while “we are seeing some early signs of improved wellbeing in 2021, we have a long road ahead to recovery and face new challenges associated with transitioning back to the workplace.”

2021: The pandemic leaves a wake of burned-out workers

Anecdotal evidence on post-pandemic employee burnout is not hard to find, and it has recently been strengthened by the results of research conducted by Jennifer Moss, Michael Leiter, Christina Maslach, and David Whiteside.

For their researchers, the team adopted the World Health Organization’s definition of burnout: “a syndrome conceptualized as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed.” Research has shown that burnout has six main causes:

Unsustainable workload

Perceived lack of control

Insufficient rewards for effort

Lack of a supportive community

Lack of fairness

Mismatched values and skills

To understand the specifics of pandemic burnout, in the fall of 2020 Moss and her collaboratorsinterviewed more than 1,500 respondents in 46 countries across various sectors, roles, and seniority levels. Sixty-seven percent of respondents worked at or above a supervisor level. In a nutshell, this is what they learned:

89% of respondents said their working life was getting worse.

85% said their well-being had declined.

56% said their job demands had increased.

62% of the people who were struggling to manage their workloads had experienced burnout “often” or “extremely often” in the previous three months.

57% of employees felt that the pandemic had a “large effect on” or “had completely dominated” their work.

55% of all respondents did not feel that they had been able to balance their home and work life — with 53% specifically citing homeschooling.

25% felt unable to maintain a strong connection with family, 39% with colleagues, and 50% with friends.

Only 21% rated their well-being as “good,” and a mere 2% rated it as “excellent.”

Interestingly, notes Moss, “millennials have the highest levels of burnout...much of this is due to having less autonomy at work, lower seniority, and greater financial stressors and feelings of loneliness.” From their analysis, Moss’ team notes several factors that led to the outcomes she and her team discovered.

1. Workloads stayed high and intense throughout the crisis.

As noted earlier, the latest productivity analysis of the pandemic suggests that workloads, especially for managers, increased significantly in 2020. Other research from Gallup has shown that the risk of occupational burnout increases significantly “when an employee’s workweek averages more than 50 hours, and rises even more substantially at 60 hours.” COVID-19 did not create the problem of long working hours, of course, but, notes Moss, “the pandemic has probably exacerbated it.”

2. Employees in many settings did not achieve the higher level of control they needed to deal with the situation

The pandemic brought employees a growing list of problems to solve — from finding childcare to dealing with isolated grandparents and bad wi-fi connections. Moreover, in many professions such as healthcare and supermarkets, employees were forced to work in high-risk settings, often with little information about the risks or control over their exposure levels.

3. Meeting volume increased, leading to unhealthy levels of screen time.

While “Zoom burnout” is sometimes treated as if it were a new phenomenon, in reality, notes Moss, “it’s just a new manifestation of a bad workplace practice on overdrive.” Moss highlights research by Steven Rogelberg (UNC Charlotte), whose pre-Covid-19 studies showed that about “55 million meetings a day were held in the United States alone and that U.S. organizations wasted $37 billion annually because most meetings were unproductive.”

4. Employers ignored the signs that many people were not coping well with the pandemic.

One of the more interesting points Moss makes is that organizations cause burnout but then treat it as a personal problem. As she notes, “we’ve put the burden of solving the problem squarely on the shoulders of individual employees.” Companies recommend “more yoga, wellness tech, meditation apps, and subsidized gym memberships” when what are needed are “upstream interventions, not downstream tactics.” Companies, notes Moss, “need to recognize that people are working unsustainably day after day, that they may not feel safe talking about their mental health, and that they’re overwhelmed and exhausted is urgent.”

What now?

Fortunately, Moss believes that there are actions we can take in response to pandemic burnout, which was the good news from her research. These actions include everything from instilling a “sense of purpose” to assigning a “manageable workload” to providing “empathetic managers.” Unfortunately for many workers, these issues are not always under their control.

Moss’ recommendations are echoed by Gallup’s researchers who suggest the following actions:

Start measuring employee well-being, in addition to engagement. “It may only require a few questions in a pulse survey, but it can help you highlight areas of concern that you can proactively address.”

Train managers to have conversations about well-being, above and beyond engagement. “Managers must be able to have appropriate but caring conversations about life outside of work if they are going to manage performance effectively.”

Capitalize on the benefits of well-managed remote work. “Managers need to be in-tune with employees' wellbeing while fostering work schedules that support productivity and work-life integration.”

Consider the disparate impact the pandemic is having on certain employees. “Front-line workers may be experiencing steep financial hardships and people from various racial and ethnic backgrounds may be facing intensified diversity, equity and inclusion concerns.”

Actively scan for signs of potential burnout. “A ‘day off’ may not be a sufficient fix in our current situation, when people need more managerial support and social connection rather than less.”

Of all the recommended strategies, perhaps the most important one is that companies allow workers to discuss mental health and burnout at work. This is an uncommon practice in most corporate settings, to say the least. Indeed, as a recent Forbes article noted: “experts find that 60% of those with a mental illness do not seek treatment” and “20% of those who do not avail themselves of mental health services at work do so out of fear it will hurt their careers.” Hopefully, the pandemic will make it more acceptable for employees to discuss their mental and psychological stresses without seeing that act as reflecting negatively on their career.

In their respective analyses, the Gallup and Moss teams agree that there is no easy fix for the burnout problems the pandemic exacerbated. Still, all managers should think about the steps they can take to recognize and address the pandemic’s legacy of burnout. Moss suggests that companies use the opportunity provided by the current pandemic to address contributing factors that probably existed long before 2020. As she concludes, “the best moment to make a move is when everything is up for grabs,” and thus it is “time to turn the change that was inevitable into the change that was always possible.”

The Research

Jennifer Moss. Beyond Burned Out. Harvard Business Review. February 10, 2021. https://hbr.org/2021/02/beyond-burned-out?ab=seriesnav-bigidea